© 2020 (Do not copy or redistribute this document)

Recovery

The preceding Chapter, History 1805-1818, ended with the calamities experienced in Newfoundland in the years immediately following 1815. Extreme weather (year without summer), economic collapse, food shortages, fires, riots all occurred during this period. Population statistics show that after a period of rapid growth between 1806 and 1816 the population of the island shrank between 1816 and 1823 and only started to grow again after 1823:

- 1806–Population of Newfoundland, estimated at 26,505.

- 1816–Population of Newfoundland, estimated at 52,672.

- 1823–Population of Newfoundland : 52,157.

- 1825–Population of Newfoundland : 55,719.

- 1828–Population of Newfoundland : 60,088.

- 1832–Population of Newfoundland : 59,280.

- 1836–Population of Newfoundland : 73,705

There are no population statistics available for Bareneed between 1817 and 1834 but it is almost certain that the population stagnated in the years following 1815. The eventual recovery can be attributed, directly and indirectly, to the Labrador fishery and the Seal Fishery (Seal Hunt). At this time a symbiotic synergy existed between the Labrador fishery and the spring seal hunt (AKA Seal Fishery in Nfld.) since both of these activities required larger vessels which might not be economical without both of these activities.

Seal Hunt

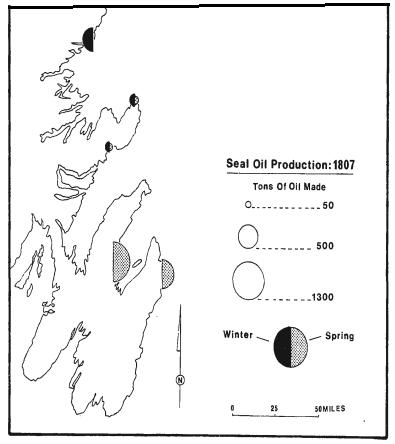

The seal hunt was initially conducted for the oil that could be rendered for the seal fat, similar to the process of using whale blubber to produce oil. The following Map from Sanger (1973) shows that in 1807 Seal Oil production was centered in Conception Bay and St. John’s with smaller amounts produced during the winter further north.

Seals were hunted on the ice flows found off northeast Newfoundland in the late winter and early spring. During this period Harp and Hood Seals gather on the ice floes in large herds to give birth.

The Seal hunt (called Seal Fishery in Nfld.) would be conducted in February to April which was a period when the coast was blocked by ice. During this period Seals can be caught from small boats, with nets set along the shore and occasionally even by walking out on the ice floes; however, having larger vessels allows fishermen to reach the main herds of seals further offshore and return with a large number of pelts (with fat). Wilson (1866, Chapter X) provides a description of the early Seal Fishery

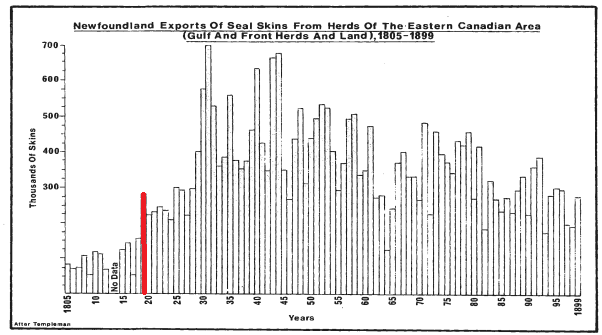

Prowse (1895) provides statistics on the Seal Fishery in Conception Bay and Harbour Grace starting in 1804 (see below, note statistics for 1804, 1805 and 1808 also track small vessels and nets).

Prowse (1895, p. 451) emphasizes the importance of the seal fishery and the resulting spin-off activities (processing the oil and Shipbuilding):

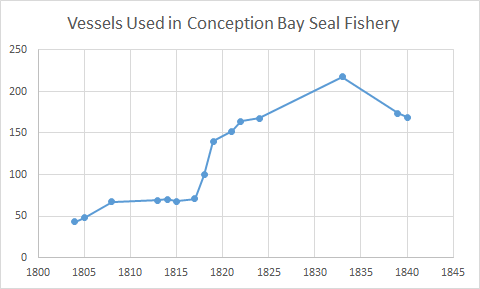

The following Graph (based on data from Prowse, 1895, p. 704) tracks the number of vessels employed in the Conception Bay and Harbour Grace seal fishery. The graph shows that between 1817 and 1819 there was a major increase in the number of vessels employed. The average size of vessels during this period remained relatively constant (between 50 and 60 tons).

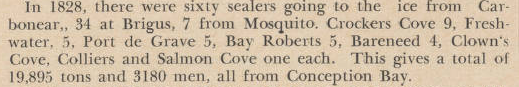

We have a breakdown by community for 1828 (from a different source) which indicates that in 1828 there were 4 sealing vessels operating from Bareneed.

Labrador Fishery

Following the post-1815 depression, increasing numbers of fishers began migrating from Newfoundland to Labrador each summer to fish there as well. The Labrador fishery served two purposes: it provided a use for sealing vessels in the off season and allowed fishers from bays where the cod stocks were depleted to still earn a living. (Source: Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador).

At first, the Labrador fishery was like the 17th century Newfoundland migratory fishery except it was now based out of Newfoundland not England. Fishermen from Conception Bay would sail to Labrador each Spring and anchor in some Bay where they would use small boats to catch cod. The cod might be processed on the boat (green fish) or dried on he shore (see separate section on Processing Cod)

However, just like the Newfoundland migratory fishery, these fishermen soon established shore bases (Rooms) where they processed their fish. The fish would be caught using row boats or “Jack Boats” (small sailing boats generally under 30′) operating from these bases. The Conception Bay fishermen would return to these room each spring and, just like the case in Newfoundland, they soon acquired rights to these rooms.

In addition to the small boats used to catch the fish the Labrador fishery also required larger vessels that could transport crews, for catching and processing the fish, and supplies (salt and food) on a 1000 km voyage to Labrador and bring these crews and processed fish back to Conception Bay. Basically, the the Labrador fishery was the same as the 17th Century migratory fishery except it was now based out of Newfoundland not England.

The previous statistics on number and size of sealing vessels up to the 1830s likely reflects the situation in the Labrador Fishery since the same vessels were used in both. The first vessels used in the Labrador fishery were small schooners of 20 -50 tons but as the as the fishery developed the size of boats increased to 60-100 tons and larger. A typical Labrador schooner might be Marilla at 50 tons and 70 feet long. Note: Tonnage is a measure of the cargo capacity of a vessel. I have prepared a separate sub page discussing Schooner Size and Tonnage.

The fishermen of Bareneed were some of the first Conception Bay fishermen to start fishing in Labrador (see reference to “Indians” from Labrador in a previous section). In 1810 the Bareneed Planter/Supplier Thomas Bartlett owned a 49 ton Schooner (built 1802 in Colliers Bay) which he used for sealing (Keith Matthews Files). A boat like this would almost certainly have been used in the Labrador fishery after the sealing season ended (April). There were other vessels based in Bareneed around this time that might have been used for sealing and in the Labrador fishery:

- Success (17 tons) owned by Edward Snow registered in 1812;

- Seaflower, schooner (no size info) , leased to James Butler by Patten, Graham & Co c 1814;

- Speedwell, schooner (35 tons) built Bareneed c 1815 by Richard Willis;

- William, schooner (37 Tons) built Bareneed 1815 owned by Edward Snow;

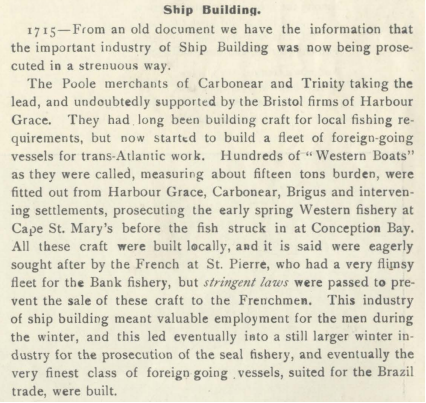

Ship Building

The following is an extract from an article by W. A. Munn published in 1935 that reviews the history of Ship Building in Newfoundland.

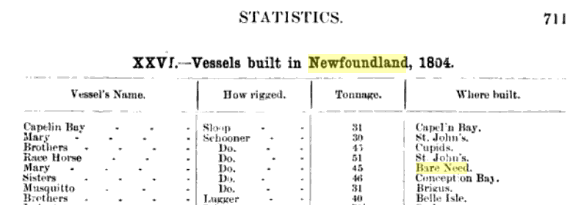

The earlest reference we have of a vessel bing built in Bareneed comes from A history of Newfoundland from the English, colonial, and foreign records by D.W. Prowse who documents that a Vessel named Mary was built at Bare Need in 1804.

Building a schooner (even a relatively small one of 50 tons) was a major undertaking that required skilled workmen, a supply of wood and financial resources (for rigging, blocks, sails, gear). In addition, catching and processing sufficient fish to fill a mid size schooner frequently would require cooperation between families. If there was an existing merchant in the community they might build/finance a schooner and give members of other families “berths” on the voyage for a share of the profits from that voyage (Sharemen). If there were several families, neither of which had sufficient resources to build a schooner, then they might pool their resources in exchange for shares of the boat (this is not a share of the voyage but shares in the boat). Even today in Canada, the property in a vessel is divided into 64 indivisible shares with 64 shares equivalent to 100% ownership. The origin of this practice has not been definitely established; however, it is a well established practice dating from the time of the British Merchant Shipping Act. Generally, one of the group would be the Captain.

Ship Registration (the documentation of ownership or title) was implemented in British colonies in the late 1700s to ensure that ships transporting goods in the British Empire were built and managed by British citizens, including citizens from the colonies. The Canadian Ship Registration database contains more than 78,000 entries of ships registered in ports of Canada (including pre. Confederation Newfoundland) between 1787 and 1966. This database includes information on the name of the ship, the type of ship, the tonnage, the port of registry, and where built. The standard query tool only allows to search on where built down to the Province; however, thanks to the Library and Archives Canada I was able to obtain data down to the town level. The following Table shows a list of ships in the database where built at Bareneed (the Mary built in 1804 was not in the Database).

| IdNumber | ConstructionYr | NetTons | VesselName | Builder |

| 67943 | 1815 | 35 | SPEEDWELL | Richard Willis owned by Graham & Co. |

| 76607 | 1815 | 37 | WILLIAM | Edward Snow owner |

| 70458 | 1818 | 50 | THORNE | Richard Baggs for Philip Corbin |

| 7968 | 1819 | 65 | BROTHERS | Edward Snow for Edward French |

| 27541 | 1819 | 67 | GOOD INTENT | Isaac Richards |

| 32140 | 1819 | 62 | HUNTER | Elias Fillyer for Thomas Bartlett |

| 34031 | 1819 | 47 | JOHN | ? |

| 77807 | 1819 | 64 | WINTER | ? |

| 4075 | 1820 | 34 | ARROW | John Batten Jr owner |

| 22843 | 1821 | 31 | FOUR BROTHERS | Benjamin Batten owner |

| 22760 | 1825 | 55 | FAVORITE | John Richards |

| 76193 | 1825 | 31 | TWO BROTHERS | John Batten owner |

| 889 | 1828 | 66 | ADVENTURE | Samuel Batten |

| 37634 | 1831 | 115 | LADY ANN | William Richards owner |

| 69860 | 1833 | 39 | UNITED BROTHERS | ? |

| 31253 | 1835 | 105 | ISAAC & ELIZABETH | John Richards owner |

| 76372 | 1836 | 80 | YOUNG HARP | Philip Corban owner |

The first ships in the database recorded as being built in Bareneed were registered in 1819 with a recorded built date of 1815. Registration of British ship started in the late 18th century but government records suggest that as late as 1816 the process was still evolving in Newfoundland.

| 29 Oct. 1816 | F. Pickmore (Fort Townshend) | Capt. Buchan | Authorizing Capt. Buchan to sign certificates of registry for vessels during Governor Pickmore’s absence. (Countersigned by P. C. LeGeyt). |

It is very likely that ships were being built in Bareneed before this date but were not registered/recorded or were being recorded as being built in Port de Grave e.g.: Hope, registered in 1794, square sterned schooner, built at Port de Grave, Newfoundland; in 1792. (Lloyd’s Register, 1795).

Starting in 1815 we start to see the first clear evidence of Ship building in Bareneed. Two small schooners (35 ton Speedwell and 37 ton William) were recorded in 1819 as being built there in 1815. In 1818 year Philip Corbin of Bareneed was recorded as owner/captain of a 50 ton schooner “Thorne“, built in Bareneed by Rich Baggs. The schooner was likely named after Thomas Thorne a Harbour Grace merchant (see Merchants Connections). In 1825 Philip Corbin of Bareneed only owned 4/64ths of the Thorne with the firm of Nuttall and Thorne owning the remainder.

In 1819 one of Thomas Bartlett Jr., registered a 64 ton schooner Hunter built in Bareneed by Ellias Fillyer (Filleul, Fillier ) another Bareneed planter (see 1805 & 1817). In 1810 his father Thomas Snr. a Bareneed Planter/Supplier owned a 49 ton schooner (built 1802 in Colliers Bay). In the same year Issac Richards built the Good Intent, 67 Tons; Edward Snow built the Brothers, 65 tons for Edward French, and two other schooners the Winter, 64 tons and John, 47 tons were registered as built in Bareneed (no other information for these two).

In the years between 1820 and 1836 nine other schooners were built at Bareneed. The ships built in the 1830s tended to be larger.

The following graph shows the number and total tonnage of schooners built in Bareneed each year:

It is perhaps not coincidental that the spike in the construction of schooners in 1819 followed the spike in spring seal catches in 1819.

The spike in construction of larger (50 ton) schooners at Bareneed in 1819, can be linked to the rapid development of this community in the next two decades. This spike allowed Bareneed to move into the seal fishery and Labrador fishery at a faster rate than larger neighboring towns. The question is why Bareneed made this move in such a decisive manner.

One factor that might have forced Bareneed fishermen to take up the Labrador fishery before their neighbours in port de Grave is proximity to the inshore cod stocks. Anspach (1818., p. 442) noted that in the Conception Bay shore fishery the distance that fishermen could travel in search of fish was limited by the tendency of fish kept too long in the boat during the summer to become soft and not easily cured. This tends to limit the distance they travel to 4-5 miles. The communities situated on the tip of the Port de Grave peninsula have a natural advantage since they have a number of fishing grounds located within this distance (from Brigus in the south, to Spaniard’s Bay in the north, to Bareneed to the west and even to Bell Island which is 9 miles to the east); while Bareneed, which is situated 2 miles further in Bay de Grave, has much less access to fish stocks. If inshore Cod stocks were becoming depleted then the fishermen of Bareneed would be the first to feel the effect and the first to look for other options.

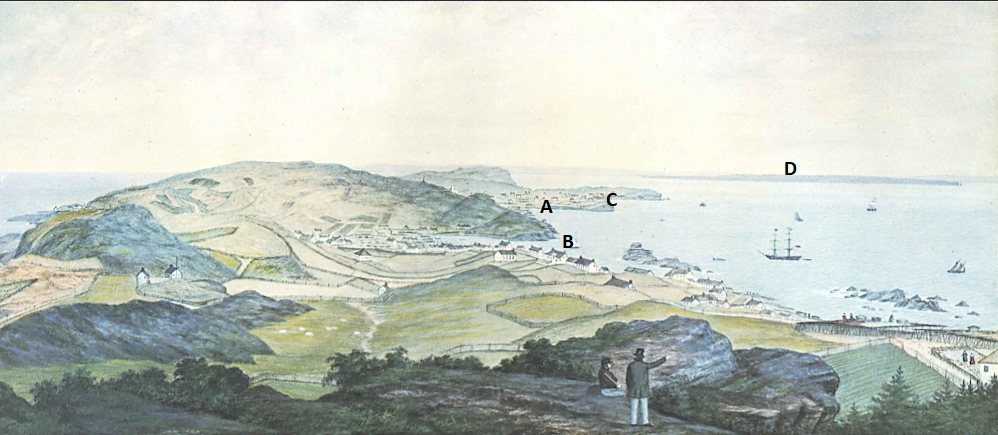

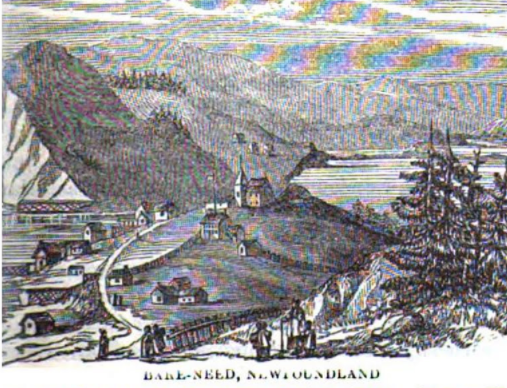

Easier access to wood for boat building could be another factor that may have made it easier for the fishermen of Bareneed to move into the Labrador fishery compared to their neighbours further out on the Port de Grave peninsula. A 50 ton schooner requires more wood and larger trees (for knees and planks) than a inshore Jack boat. A sketch of Port de Grave c 1841 (see below) shows that this area was cleared of forest well before this date.

A sketch of Bareneed c 1851 (see below) suggest that even at this later date there were wooded areas on the hills behind the Dock (immediately to the west of Bareneed).

Even today the hills behind the Otterbury (just west of the Dock, Bareneed) are forested (see below)

In 1839, Joseph Jukes a geologist working for the Newfoundland government commented on the trees at Northern Gut (just west of Bareneed): I was much struck with the beauty of the little valley we had visited, its sheltered situation between two bold rocky ridges, and the apparent superiority of the soil on the Banks of the pond and brook, as evinced by the larger size of the trees

The boom in the shipbuilding industry in Bareneed between 1818 and 1837 was likely driven by demand for larger schooners driven by the expansion in the Seal Fishery and the Labrador Fishery. This was further enabled by a supply of timber in areas immediately west of Bareneed (the Dock, Otterbury, Black Duck Pond and Northern Gut).

1833 Murder of John Snow of Bareneed

This section under construction

The History of Bareneed is continued in the next section History 1837-1901

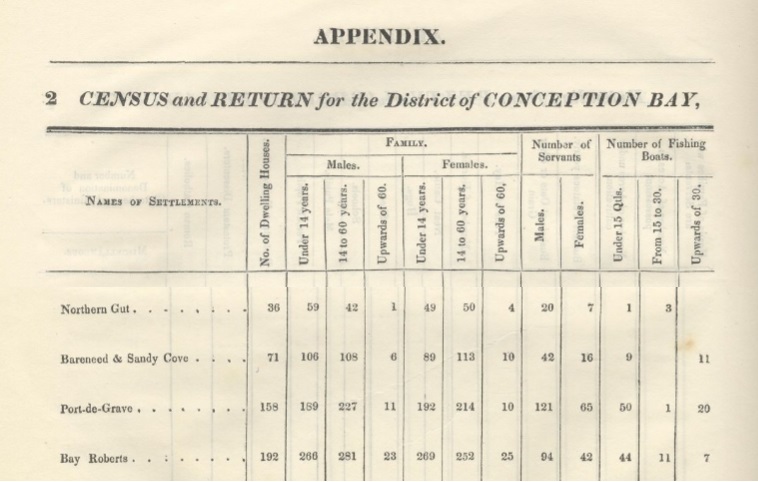

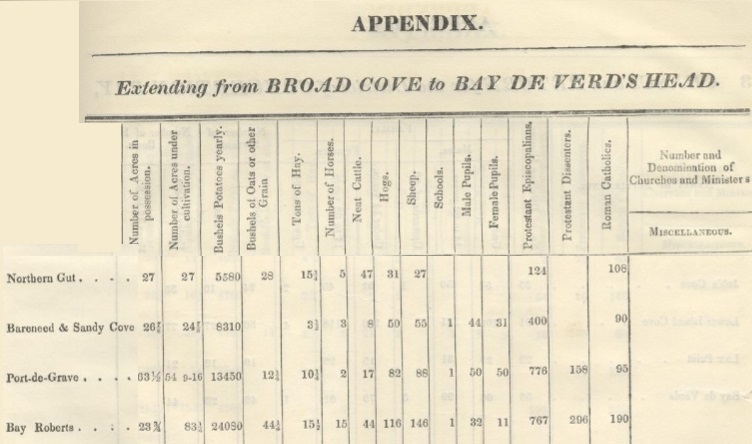

The following Tables give the results of the 1835 Census for Bareneed and the surrounding towns (Note: Bareneed stats include Sandy Cove on the western end of Port de Grave).