Descent into Darkness

© 2020 (Do not copy or redistribute this document)

Introduction

This Chapter is a sub section of the part of my Web Site dealing with the town of Bareneed, Newfoundland (see main Menu of this site). That section of the Site provided an overview of Geography, Population, Religion, Education and Economy. This Chapter is the second of a series of sub sections that focus on the History of Bareneed. These subsections are organized chronologically from 1497 through to the 1950s.

The first Chapter in the History section Bareneed 1497-1805 ends with a discussion of the 1805 Plantation Book which tends to paint a picture of an established and prosperous community. On the surface a census compiled in 1817, just 12 years later, would appear to show a similar picture. However, this was not the case (see below).

Census of 1817

The 1817 Census of Bareneed Number of inhabitants in the Harbour of Brigues, Cupids, Bear Need and Port de Grave ending September 27th 1817 was compiled by Capt David Buchan RN. The Survey was organized by town (Port de Grave, Bareneed, Cupids, Brigus) with Bareneed (Bear Need in report) including people living at the head of Bay de Grave (Otterbury, Northern Gut, Clarke’s Beach, Southern Gut and Salmon Cove).

The following Table presents the population information in the 1817 Census for Bareneed. The Table was compiled from the transcription on the Newfoundland’s Grand Banks Web Site. The 1817 census not only listed householders but also included statistics on their wives, children and servants (M & F). I have restructured the population data into three categories: Children, Servants (now includes M & F) and Total:

| # | Name | Children | Servants | Total |

| 2 | Th’s Boon Senr | 3 | 5 | |

| 3 | Ab’m Boone | 4 | 6 | |

| 4 | Jacob Hall | 3 | 4 | 9 |

| 5 | Th’s Boon John Son | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| 6 | Th’s Boon Wm Son | 4 | 6 | |

| 7 | Wm Boone | 1 | 3 | |

| 8 | Ch’s Boone Abm Son | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| 9 | Th’s Boon Junr | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 | John Boone Abm Son | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 11 | Ben Batton | 5 | 1 | 8 |

| 12 | Sam Batton | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| 13 | John Batton Wm Son | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| 14 | John Batton Sam’l Son | 5 | 4 | 11 |

| 15 | Edw’d Snow E son | 6 | 8 | |

| 16 | Wm Snow ditto | 2 | 4 | |

| 17 | John Snow ditto | 6 | 8 | |

| 18 | Wm Snow Senr | 4 | 6 | |

| 19 | John Snow | 2 | 3 | |

| 20 | Edw’d Snow W Son | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 21 | Th’s Snow E Son | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 22 | Ch’s Morgan | 2 | 4 | |

| 23 | Thomas Snow Snr | 1 | 3 | |

| 24 | Elias Picco | 2 | ||

| 25 | Jacob Delany | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 26 | John Boon Son Th’s | 5 | 7 | |

| 27 | Th’s Bartlett Senr | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| 28 | Isaac Richards | 4 | 4 | 10 |

| 29 | Wm Bartlett | 7 | 9 | |

| 30 | Th’s Bartlett Junr | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| 31 | John Bartlett | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 32 | John Richards Senr | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| 33 | Elias Filleul | 4 | 6 | |

| 34 | Isack Filler | 2 | ||

| 35 | Abr’m Filler | 2 | ||

| 36 | John Filler | 2 | ||

| 37 | John Moore | 2 | 9 | 13 |

| 38 | Sam’l Stephens | 4 | 6 | |

| 39 | Benj’m Stephens | 2 | 4 | |

| 40 | Hard Stephens | 2 | 4 | |

| 41 | John Bucham | 5 | 3 | 11 |

| 42 | John Curlew | 2 | 3 | |

| 43 | Benjamine Curlew | 6 | 8 | |

| 44 | Samuel Curlew | 1 | 3 | |

| 45 | Dan’l Deleany | 5 | 7 | |

| 46 | Sam’l Bradberry | 4 | 6 | |

| 47 | Batt Corbin Senr | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 48 | Batt Corbin Jnr | 2 | ||

| 49 | Phil Corban | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| 50 | Edward French | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| 51 | James Butler | 4 | 6 | 12 |

| 52 | Wm Turner | 5 | 7 | |

| 53 | Philip Nule | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 54 | Isaac Daw | 1 | 1 | |

| 158 | 321 (6.1 avg) |

The data for Bareneed was listed in two sections; the first group starting with #2 Thomas Boon Senior (#1 blank) who likely lived just east of the current wharf and going east to Jacob Delaney (#25) in the east end of Bareneed. The second group starting with John Boone (#26), who likely lived west of Thomas) and running in a general east to west direction (counter clockwise around the Bay). I have assumed, based on my research, that Isaac Daw (Dawe) was the last resident of what is now Bareneed and that the remaining people in the list (not included in Table) were living in what is now the Otterbury, North River, Clarke’s Beach and Salmon Cove.

The Table demonstrates that between 1805 and 1817 the population of Bareneed had increased from an approximate estimate of 184 in 1805 to 321 in 1817 an increase of perhaps as much as 76% (only slightly lower than the rate of increase for all of Newfoundland). However, the truth is that the 1817 census was compiled to help address a crisis that had developed due to natural and man made causes.

The most significant man made factor that led to economic problems in Newfoundland during this period was the end of the Napoleonic Wars. This conflict had increased demand and prices for Newfoundland fish; however, with the coming of peace in 1815, foreign competitors reappeared, and import tariffs began to affect Newfoundland’s salt fish exports. These lower prices meant that local fishermen like those in Bareneed received less for their catch than they expected and since they generally bought their supplies from the Merchants on credit they ended the season owing money to the Merchant.

This man made crisis was compounded by natural events. In 1815 the Mount Tambora volcano in Indonesia erupted producing the most powerful volcanic eruption in human recorded history. This eruption ejected so much debris into the atmosphere that it caused a global climatic cooling in 1816 that became known in Europe and North America as “The Year Without a Summer.” In parts of New England there was snow in every month of that summer and there were major crop failures in North America and Europe. In eastern Canada, the cold spell’s most profound, immediate impact was that the price of flour soared throughout the colonies. In Newfoundland the problem was less of an issue of crop production (which was minimal at that time) but more of an issue with decreased imports of food from England and a general depression of the global economy.

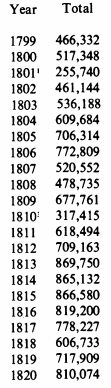

There is no indication that Cod catches in Newfoundland were significantly depressed in 1816 (see following Table); however, the rapid increase in population from 1805 to 1817 (see previous discussion) would suggest that catches per fisherman were decreasing due to over-fishing.

Fishery to Colony: A Newfoundland Watershed, 1793-1815

Apart from the shortages of imported food and high price for food the second most important impact in Newfoundland was that the winter of 1817 was especially cold which placed an additional strain on a population that was under fed. The fallout from the bad weather was compounded by the depressed markets, limited resources (supplies, money and troops) available to the Governor in St. John’s and the tendency of the Merchants to look out for their pocket books and ignore the plight of local planters and servants.

Bareneed Merchants 1817

The Census of 1817 was relative unique among early Newfoundland censuses in that it not only listed householders but also included the name of the supplier (merchant) each planter used and provided a general indication of their economic state (e.g. Well Off, Distressed). The following Table presents a list of the Merchants operating in Bareneed and the number of planters they supplied (the full Table is on a separate page).

| Supplier | Base | # Clients |

| Bartlett, Thomas | Bareneed | 13 |

| Graham (& Co.) | Scotland & Bareneed | 10 |

| Moore, John | Bareneed | 7 |

| Pack, Likely Robert | Bay Roberts | 6 |

| Johnston, William | Scotland & St. John’s | 4 |

| Natale & Cawley | Harbour Grace | 4 |

| Danson, Wm. | Harbour Grace | 3 |

| Pincent, William | Port de Grave | 2 |

| French, Edward | the Dock / Bay Roberts | 1 |

| No Data | 2 | |

| Sundry | 1 |

This list is somewhat misleading since in some cases there was an hierarchy of Merchants. For example, seven planters used John Moore as their merchant; however, John Moore the planter (also likely the merchant since he had 9 servants) list Pack has his Merchant; Bartholomew Corbin Jr. list Edward French has his Merchant but Edward French list Graham has his.

The supplier listed as Graham in the Census was a group of Scottish merchants that operated under a variety of names in Newfoundland and Scotland. At the time of the 1817 Census this company was operating as Graham, McNicol & Co. and directly supplied 10 planters in Bareneed (this company is discussed in more detail later in this report).

Thomas Bartlett Snr. had the greatest number of direct clients in Bareneed. Thomas was listed in 1805 Plantation Book has receiving his property in Bareneed from his Father in Law in 1778. In 1817, Thomas and his three adult sons lived at the bottom of Shop House Hill in Bareneed Cove (see Photo above). Thomas only had 2 servants but likely relied on his large extended family to run his business. In 1817 Thomas was listed as “Well Off” and using “Sundry Merchants” as his supplier. This suggest that he was not tied (through credit) to one supplier.

John Moore was one of the last planters in Bareneed. His plantation (likely in the Back Cove, facing Bay Roberts and west of the current church ) is listed as Cut and Cleared 1804 in the 1805 Plantation Book. There were no buildings recorded at that time so he likely occupied the plantation around this time. By 1817 he had a wife, two children, 8 male servants and one female servant and is listed as “Well Off”. As indicated earlier 7 other planters reported him as their Supplier but he listed Pack as his. Moore was a Constable at Bareneed and in 1815 he was sued for building part of a house (incomplete contract). Moore was involved in some minor court cases (generally over access to land).

Mr. Pack (Likely Robert from Bay Roberts) is listed as W. Pack in the transcription on the Newfoundland’s Grand Banks Web Site. However, my interpretation is that the original was Mr Pack. There is no good candidate for a W. Pack but Robert was a established merchant in Bay Roberts at that time. The Census of 1817 either did not cover Bay Roberts or the data is lost.

William Johnston was a Scottish merchant who at this time was based in Port de Grave. A Thomas Patten (see more below re links to Graham), and John Hamilton established a fish export business in St. John’s, initially registered as Laing, Baine & Co., Greenock. In 1814 the partners were Lang, Walter Baine Jr., and William Johnston. That year the firm constructed premises at Port de Grave, Newfoundland. Lang retired in 1831, and the firm became Baine, Johnston & Co. in 1832.

The firm listed as Natale & Cawley was Nuttall & Cawley, Harbour Grace fish merchants. Nuttall was John Charles Nuttall born 1791 at Bristol, Gloucestershire. Mr Cawley, the second principal in Nuttall and Cawley, was a member of the Cawley family of Bristol and Harbour Grace; however, it is not exactly clear which Cawley was involved in the partnership with Nuttall. This firm was the supplier for 4 planters in Bareneed including my ancestor Philip Noel/Newell so my Merchant Connections Web Page provides more information on this firm.

William Danson (2 clients) was another Harbour Grace merchant based in Bristol (who apparently had houses at Liverpool and Bristol, besides in Newfoundland). William wrote his Will in 1816 but the business continued under his son Hugh William Danson a merchant of Harbour Grace who went bankrupt in 1831. Hugh W. Danson, of Bristol and Harbour Grace, also had operations at Holyrood and Bay de Verde. There was also a younger son Thomas Elias Danson mentioned in the 1816 Will of William Danson who may be the person mentioned in the following report:

Early in April, 1817 a sealing schooner belonging to Thomas Danson, a

merchant of Harbour Grace, blew up a few miles off Cape St. Francis, at the

mouth of Conception Bay. The vessel was most likely returning from the

icefields with a load of seal pelts at the time the tragedy occurred, though

she could have been just starting out on her second trip… Most of the crew of the schooner were either killed outright or seriously injured. The

captain of the ill-fated craft was John Newall or Noel, a well-known Harbour Grace name [likely from Brigus]. He was mortally injured in the explosion and died the same day as he was landed in Harbour Grace from a rescue ship. Source: Evening Telegram January 11, 1960 Off Beat History. Tragedy on Sealing Schooner.

William Pincent (2 clients) was another Port de Grave merchant.

Edward French, who was only listed as the supplier for Bartholomew Corbin Jr. could have been Edward French from the Dock or Edward from Bay Roberts; however, the latter is more likely since Edward French from the Dock was described as “Bad Off” and listed Graham has his supplier.

Winter of the Rals in Bareneed

The winter of 1817 became known as the winter of the Rals (rioters) in Newfoundland. It was a season of famine, extreme cold, fires in St. John’s and riots (rals) in various parts of the island. Roiters broke into stores of provisions when merchants refused to give the servants provisions on credit. The storekeeper of Patten, Graham & Co. , Duncan McKellar. Stated that when the mob approached him at the store at Bareneed on 3 February, one of its leaders Nicholas Nevil [planter at Northern Gut] shaking his hand in my face, said that as we had not given him provisions at the fall of the year, insinuated that he would have it by force… . On hearing that McKellar hoarded food in his house, the mob deputed five to six men to search it, and they found food in the bedroom, taking bread and pork (Sean Thomas Cadigan, 1991).

On March 11, 1817 a group of Conception Bay merchants wrote to Lord Bathurst: Severe shortage of provisions in Nfld threatens famine and has led to “plundering & destruction” of their property. The petitioners trade into Conception Bay where there is no military force in the district. The worst dangers were “arrested by the active exertions of the respectable inhabitants” but they fear worse. A request to the military in St. John’s was ineffective because conditions there were also bad. Request “some Force” be sent to Conception Bay to protect relief shipments being sent. There are too many people in Nfld for the merchants to support (CO194-60).

Through the effort of the Naval Governor, Vice Admiral Francis Pickmore, who died in office at St. John’s on 24 Feb. 1818, and Commander David Buchan but with little support from London the Island made it through the worse period in it’s 500 year history. Pickmore was literally worked to death by his efforts to alleviate the worst sufferings. He placed a temporary embargo on all vessels holding supplies, purchased provisions wherever possible, and sent out urgent appeals for help; subsequently, substantial aid came from Halifax, N.S., Boston, Mass., and England. (DCB) Prowse in his 1896 History of Newfoundland heaps praise on Buchan.

Fortunately, at this terrible crisis, the virtual control of the Colony was in the hands of Captain David Buchan, R.N. The most fulsome panegyric is really but faint praise for the cool courage, able management, and humane exertions of the heroic commander.

Buchan, who was in command of HMS Pike (a 14 gun Schooner), was the interface between the Crown and the fishermen of Conception Bay. It was Buchan who was responsible for collecting the information for the Census of Conception Bay conducted in 1817 and despite his role in the Lundrigan affair (see below) there is lots of evidence to support Prowse’s description to him. Perhaps, the most telling praise came from the following source:

29 Jun 1817, J. Macbraire, President of the Benevolent Irish Society to D. Buchan, Attached: This document is very faint. From what can be made out, the author transmits a copy of the Benevolent Irish Society’s resolution praising Buchan for his meritorious conduct during the past winter, at which time he was captain of the HMS Pike (CO194-93).

The Scottish Merchants

The Supplier/Merchant referenced as Mr. Graham in the 1817 Census of Bareneed (see earlier discussion) was Graham, McNicol & Co. of Bareneed and Scotland.

Before the winter of 1817 the company operated as Graham, Patton & Co. of Bareneed and Graham, Patton & Co. of Greenock, Scotland and the principals were Alex Graham and James Patton in Scotland and Thomas Patton Jr in Bareneed. This Thomas Patton was likely the Thomas who in 1812 had been a partner with Peter MacPherson and others in a company operating out of Port de Grave.

In 1811 this Peter MacPherson (bachelor of Greenock) married Lucinda Furneaux of Port de Grave with Thomas Patten as a witness. Lucinda was the daughter of JosephFurneaux, the agent for Newman and Co. at Port de Grave. This is also likely the Thomas Patton who in 1806, established a fish export business in St. John’s with Thomas Lang, Walter and Archibald Baine, and John Hamilton , initially registered as Laing, Baine & Co., Greenock. In 1814 the partners were Lang, Walter Baine Jr., and William Johnston. That year the firm constructed premises at Port de Grave, Newfoundland. William Johnston, one of the partners in this group, was a supplier for several planters in Bareneed in 1817. Lang retired in 1831, and the firm became Baine, Johnston & Co. in 1832 (a famous Newfoundland Co. based at St.John’s).

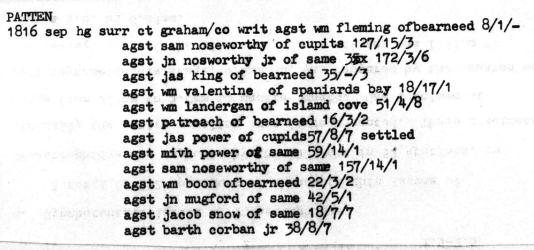

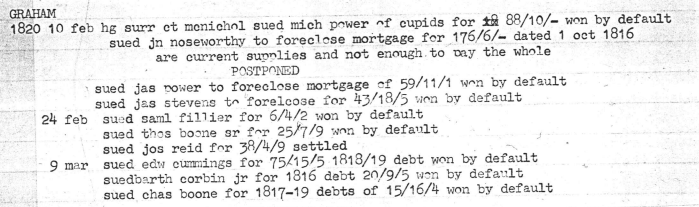

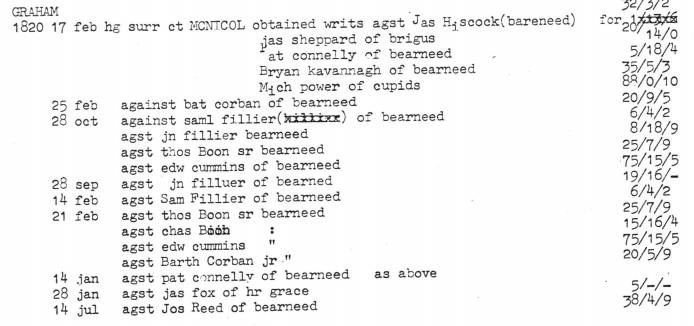

The economic fallout from the the events of 1816-1817 reverberated through the community of Bareneed . The following is a list of the fishermen that Patten, Graham & Co. obtained court writs against in one month (Sept 1816). Many merchants were taking out writs against their clients during this period but Patten, Graham & Co. was particularly aggressive. Being based in Bareneed [known as Bearneed during this time] they had many of the local Planters as clients which hit the community very hard.

Being indebted to Patten, Graham & Co. could lead to ruin for a planter (see below):

In consideration of my being indebted to Patten Graham & Co. Merchants in Bareneed in the sum of forty three pounds fifteen shillings and nine pence sterling I hereby make over unto the said Patten & Co. all my right title and interest in a fishing Room I hold in Harbour Main with the buildings thereon as at present occupied by me consisting of a dwelling House, Stage, Flakes etc. I also make over unto the said Patten & Co. two fishing skifts with all their materials until such time as I shall redeem said sum of forty three pounds fifteen shillings and nine pence sterling and pay it to said Patten & Co. as witness my hand in Bareneed this 28th day of November 1815.

Patrick (his x mark) Cahill

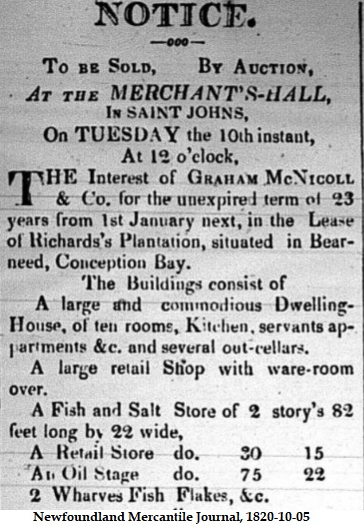

Patten, Graham & Co. was dissolved in Feb 1817 and the company was then reformed as Alex Graham & Co operating with with John McNichol and Duncan McKellar. In the winter of 1817 Patten, Graham & Co. operated a store at Barneed and Duncan McKellar was their storekeeper (see previous discussion of his role in the riots at Bareneed in February 1817). In May 1814 Abraham Richards had leased his land to Thomas Patton & Co. (in October, 1820 Graham, McNichol & Co. sold the 23 years remaining on this lease).

There is no direct evidence but their store in Bareneed was likely situated on land owned by Abraham Richards in 1805. If so this store would have been situated near the house in Bareneed where I grew up (prior to 1912 this house had belonged to the Richards family).

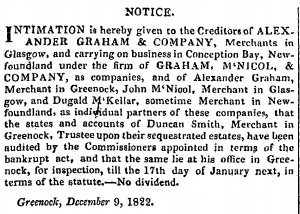

The continued fallout from the events of 1817-18 was too much for Graham, MacNicoll, and Company. In June of 1819 the company went into bankruptcy in Scotland:

ALPHABETICAL List of Scotch BANKRUPTCIEs, announced between 1st and 31st July 1819, extracted from the Edinburgh Gazette. Graham, Alex. and Company, merchants, Glasgow, and carrying on business at Conception Bay, Newfoundland, under the firm of Graham, MacNicoll, and Company; and Alex. Graham, merchant in Greenock, and John M’Nicoll, merchant in Glasgow, the individual partners there of (source: https://books.google.ca/books?id=CNwEAAAAQAAJ ).

In 1820 Graham, McNicol & Co. (or their receivers) took out writs against many of their clients in Bareneed.

By May of 1820 it appears that Graham and McNicol had suspended their business in Bareneed.

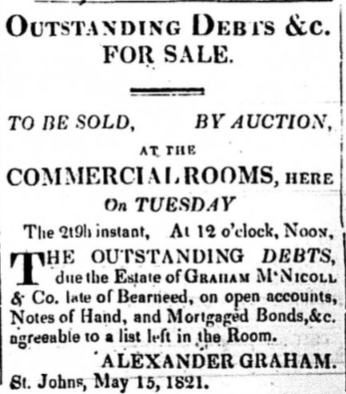

In October, 1820 Graham, McNichol & Co. sold the 23 years remaining on the lease they had on Abraham Richard’s property in Bareneed (in May 1814 Abraham Richards had leased his land to Thomas Patton & Co.) . In May 1821 the debts of Graham, McNichol & Co of Bareneed were sold off.

By June 1821 Graham, McNichol & Co. of Glasgow was in receivership in Scotland.

In April 1822 an Alex. Graham, merchant died at Glasgow and the last reference I have found to the company was in December 1822.

The James Lundrigan Case

One particular case involving Graham, McNicol & Co. got James Lundrigan, a poor planter, an entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and a place in Newfoundland Judicial history. The story started with Graham and partners issuing a writ against Lundrigan in May 1819.

Issuing writs against clients was nothing unusual for Graham; however, in this case a mountain did develop from a Molehill. Some highlights of the case from the DCB entry are as follows:

A constable then proceeded to Cupids and attached Lundrigan’s room together with “a boat and craft”; these attachments were made for two executions, one against Lundrigan himself and another as security for James Hollahan,. Together the debts amounted to over £28. Lundrigan’s property was sold to Donald Graham, a clerk in the employ of the creditor [my emphasis JN]. After the sale an attempt was made to take possession of Lundrigan’s house, but the fisherman was not at home and his wife threatened “to blow” a constable’s “brains out.” Whereupon the seizure of the property was deferred to another date.

Graham, McNicol & Co went Bankrupt a few months after this event so the case likely went into limbo until the following season (see DCB entry below):

A year later, on 5 July 1820, a surrogate court sitting at Port de Grave (or at Bareneed) summoned Lundrigan to appear before it, but he declined to attend. Constable William Keating later testified that Lundrigan “said he had no shoe to his foot and was nearly naked, and was ashamed to appear before gentlemen in the Courts… The next morning Lundrigan was brought ashore at Port de Grave to appear before Buchan and a recently appointed surrogate, the Reverend John Leigh, Anglican priest at Harbour Grace… A summary conviction was made after Kelly’s testimony, and Lundrigan was sentenced by Leigh (with Buchan concurring) to receive 36 lashes on the bare back. It was further ordered that Kelly, “with such assistance as he shall find necessary,” take possession “this day” of Lundrigan’s premises. The order meant, in effect, the immediate eviction of Lundrigan’s wife and four young children

The boatswain’s mate of the Grasshopper inflicted 14 lashes with a cat-o’-nine-tails, at which point Lundrigan fainted and Shea [the Doctor at Port de Grave] “desired the punishment to stop.” The victim was cut down and taken into the house in which the court had sat, where, in Shea’s words, “he appeared much convulsed.” According to the court records, the remainder of the sentence was remitted on Lundrigan’s “promising to deliver up the premises without further trouble.”

The treatment given to Butler and Lundrigan provoked deep outrage in Newfoundland and quickened the movement for reform [see below]. On 8 and 9 Nov. 1820, with the support of the reform party, Butler and Lundrigan made the extraordinary move of taking out actions of trespass for assault and false imprisonment against Buchan and Leigh in the Supreme Court of Newfoundland.

In November 1820 the Judge and Jury found for the Defense – no remedy in Law- but the case was appealed to the Privy Council, in London on the Advice of the Chief Justice (Keith Matthews files). After the trial, Leigh offered a settlement (see below).

A report published in 1821 (see following) made the case for reform.

Some details of the case not in the DCB entry but in the above are as follows: Landergan was taken in a boat to Bearneed, and put on board his

Majesty’s Ship Grasshopper, where he was kept a prisoner during the night. The next morning the Grasshopper removed to Port de Grave, where a Court was opened.. Landergan was charged with divers contempts of Court, and resisting Constables in the execution of their duty, and

particularly with refusing and neglecting to attend the Surrogate

Court held at Bearneed, on the preceding day.

Despite its notoriety the Landrergan case was just the tip of the iceberg of the problems that were occurring between the Scottish Merchants operating in Bareneed and their clients.

The Story of the “Indians” under the Shop

There is one other event that occurred at Bareneed during this time period that is noteworthy and I have a very thin thread connecting me to this event. The Indigenous Beothuk people who lived in Bay de Grave before the first Europeans arrived had disappeared from this area by the start of the 17th century but this did not end connections between Bareneed and Indigenous Peoples. As a boy growing up in Bareneed in the 1950s it was not uncommon to spend a Saturday afternoon sitting on the attic steps of Harry Greenland’s general store listening to older men standing around the stove telling stories. A favorite story of Mr. Harry Greenland, the store owner b. 1899, was one about the “Indians” buried under the store. The story was that when his father built the store (19th century) they had to move the “Indians” buried there. At the time I assumed that it was part of one of the typical ghost stories that one might hear at the time. Moving forward to early 1970s and I was an undergraduate student at Memorial University and did a course in Rural Settlement taught by Prof. John Mannion. Part of this course was doing a research paper on your home town and family history (start of my research on the Newell family of Bareneed) . To my surprise I found that there was an historical basis for this story (see following).

Based on the following description of their clothing I concluded that they were likely Inuit (correct name for people generally referenced as Eskimo in historical documents). The Innu people of Labrador (previously called Montagnais/Naskapi Indians) are a separate ethnic group that live inland from the coast.

By this period most Labrador Inuit had been converted by Moravian Missionaries (the Moravian Mission at Hopedale was established in 1782) while the Innu (“Indians”) were Roman Catholic (converted by Roman Catholic Missionaries from Quebec).

Some later researchers have suggested that Mr Bartlett, who brought the “Indians” to Bareneed was one of the many Bartletts from Brigus since there was a “Marg (An Indian woman)” buried at Brigus in 1810. However, there were several Bartletts living in Bareneed at this time including Thomas Bartlett who was a local Merchant (see earlier discussion). In 1810 this Thomas owned a 49 ton Schooner (built 1802 in Colliers Bay) which he used for sealing (Keith Matthews Files). A boat like this was almost certainly used in the Labrador fishery after the sealing season ended (April).

After researching the source Journal, I suspect that Mr Neale in this copy was Mr. Nuel my 3X Great Grandfather (Philip Noel / Nuel/ Newell) or his eldest son James (b. 1786); Philip’s other son my 2 X Great Grandfather John (b. 1793) was likely too young. This event is evidence of early connections between Bareneed and the Labrador fishery and perhaps even Labrador fur trade (Mr Neal /Nuel).

The story of the Bareneed “Indians” does not have a happy ending since the local story is that these individuals died of Smallpox and were buried in Bareneed.

Recovery

The preceding discussion highlighted the calamities experienced in Newfoundland in the years immediately following 1815. Extreme weather (year without summer), economic collapse, food shortages, fires, riots all occurred during this period. Population statistics show that after a period of rapid growth between 1806 and 1816 the population of the island shrank between 1816 and 1823 and only started to grow again after 1823:

- 1806–Population of Newfoundland, estimated at 26,505.

- 1816–Population of Newfoundland, estimated at 52,672.

- 1823–Population of Newfoundland : 52,157.

- 1825–Population of Newfoundland : 55,719.

- 1828–Population of Newfoundland : 60,088.

- 1832–Population of Newfoundland : 59,280.

- 1836–Population of Newfoundland : 73,705

The next Chapter of this report, History 1818-1837, discusses this period of recovery.