Tracking the Deep Roots of my early Newell Ancestors

As I indicated in the Introduction to my DNA report the Y-DNA from the 23rd sex chromosome found in males is passed down from father to son (like traditional family names) so it is frequently used in genealogical research to trace family history. Essentially, what these test do is look for small changes in the DNA that are specific to a group of people (either large group like Western Europeans or a small group like a family). These changes are technically mutations but remember that these mutations are a normal process that is continually occurring in all organisms and that in almost all cases have neither positive or negative effects. There are two different types of changes that these test track.

The first is looking for small changes in DNA coding called single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), these are variation in a single nucleotide that occurs at a specific position in the genome (see: http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/precision/snips/). Basically, these are changes in the underlying coding units for DNA which are generally represented by the letters A,C,T and G. Changes in this coding happen relatively infrequently in all individuals and subsequently get passed on to their children. In genealogical DNA research they look for changes in SNPs that are associated with different populations of people which indicate that some distant ancestor of this group had this change and it got passed on to all his (Y-DNA) children. This is refereed to as the founder effect (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Founder_effect ). An analogy might be looking through millions of copies of a best selling book looking for a specific letter in a word on a page (Typo) that differs between copies. This difference would indicate that copies with this typo were produced in a different version/edition of the book. In medical DNA they use a similar technique to search for changes in SNPs that are associated with a particular disease; normally these are different SNPs from those used in genealogical research.

Changes in the SNPs used in anthropological / genealogical research can be used to track the movements of people over long time frames (movement out of Africa ~100,000 yr BP) or shorter time frames (formation of Irish clan groups within the past few millennia). We all carry DNA markers that trace our origins in Africa and for most Europeans even our Neanderthal ancestors. Researchers have classified different groups of people around the world into groups based on their SNP markers. These groups are referred to as Haplogroups (see: https://isogg.org/wiki/Haplogroup ). Not only can SNP markers track the origin of a group of people they provide a road map of how these people dispersed since subsequent mutations in other SNP can be used to track their movements.

National Geographic DNA Test

In 2012 I did the National Geographic DNA test (Genographic 2.0) which test SNP markers for Y-DNA (males only) and mtDNA (see Intro to DNA Section for more info on mtDNA). The results of the National Geographic Y-DNA test indicated that I was positive for the L21 SNP which puts me in the L21 Haplogroup which is a subgroup of the larger R1b Haplogroup. The majority of people of European ancestry belong to either the R1b Haplogroup or the closely related R1a Haplogroup and share a significant proportion of their DNA markers with ancestors that lived in the area near the Caspian Sea during the last Ice Age ~25,000 years BP. The SNP mutations that define the R1a and R1b Haplogroups developed in this area and the people who carried these mutations started migrating into Europe after the last Ice age. The following Map shows more detail for the movements of people as they moved into Europe..

Source: https://www.familytreedna.com Note: maps like these change as new research is conducted.

The R1a group had its origins (change in SNPs) around 20,000 yr BP and people with this SNP took a route that resulted in them having the highest modern frequency in Eastern Europe (Slavic areas); however, some R1a individuals migrated south into the Middle East and India. Another branch took a later more southerly route into Europe (possibly passing north of the Black Sea) and then moved north into Western Europe; this group, which I belong to, is classified as R1b. The people carrying the R1b SNPs were not the first modern people to move into Western Europe but today Western Europe is dominated by the downstream subclades of R1b. It should be noted that once you move into subclades (subgroups) of a Haplogroup the current methodology is to identify them by the code for the specific SNP that defines them (e.g M269). Sometime after the R1b (M269) people had started their migration into Europe (around 5500 BP) they separated into more subgroups (identified by SNPs).

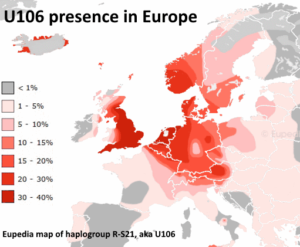

The subgroup of R1b identified by the SNP S21 commonly referenced as U106 moved north into NW Europe and is now the most frequent group in the Germanic parts of Europe.

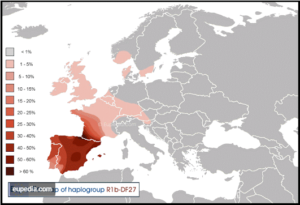

A second sub group of R1b identified by the marker DF27 (also known as S250) moved south into southwestern France and the Iberian peninsular.

Research by Neus Solé-Morata et. al. (2017) found that R1b-DF27 is present in frequencies ~40% in Iberian populations and up to 70% in Basques, but it drops quickly to 6–20% in France. Overall, the age of R1b-DF27 is estimated at ~4,200 years ago, at the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, when the Y chromosome landscape of W Europe was thoroughly remodeled. They further concluded that NE Iberia is the most likely place of origin of DF27. Subhaplogroup frequencies within R1b-DF27 are geographically structured, and show domains that are reminiscent of the pre-Roman Celtic/Iberian division, or of the medieval Christian kingdoms.

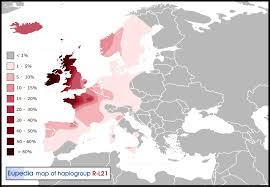

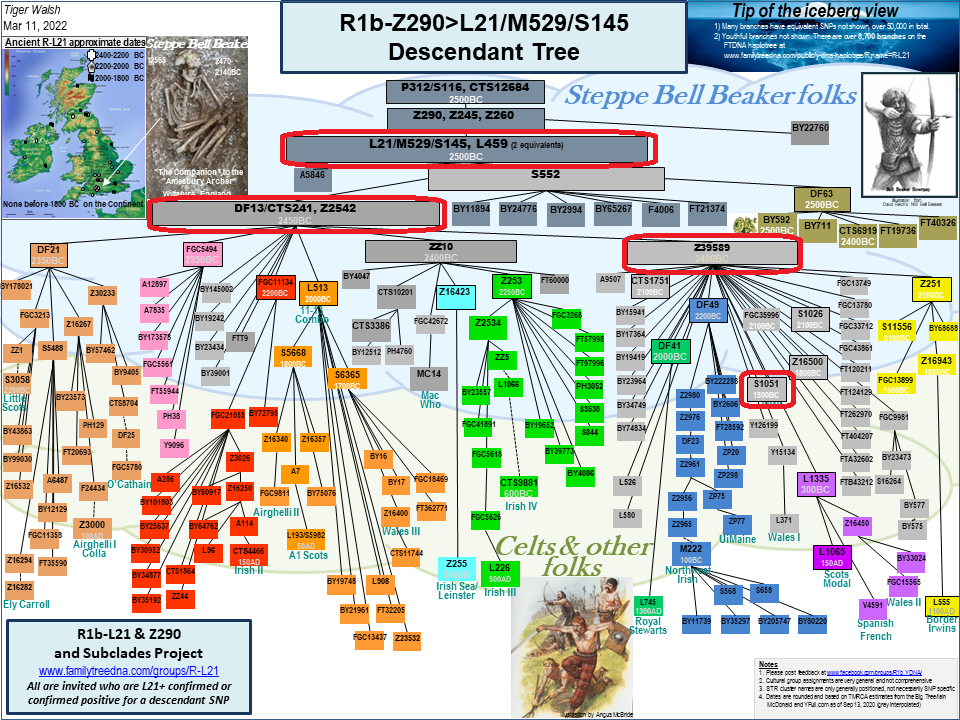

A third sub group L21, which I belong to, likely had its origins somewhere in Europe, probably in the Alpine region in the vicinity of the headwaters of both the Danube and the Rhine but subsequently migrated west into France, the Netherlands, the UK and Ireland (see below). It is likely that the Proto-Celts who migrated to the British Isles c 2500 BC belonged to the L21 subclade of R1b, as this haplogroup now makes up over two thirds of paternal lineages in Wales, Ireland and Highland Scotland. It should be noted that there is some controversy regarding the origins and migration routes for L21 , with alternate theories speculating an origin in the Basque region of Spain and others suggesting an Irish origin.

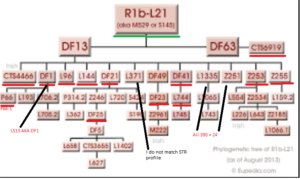

People with the L21 SNP likely arrived in Britain and Ireland around 4500 BP in association with the arrival of the Bell Beaker Culture. The new arrivals appear to have displaced the previous male residences and and relatively quickly became dominant Y-Haplogroup. However subsequent migrations of Anglo Saxon people (including the U106 Haplogroup referenced earlier) supplanted L21 males in much of England and coastal Europe; however, L21 remained the dominant Haplogroup in Ireland, Wales, Scotland and Brittany. Lower levels of L21 in the Netherlands and along the Rhine River in Germany may reflect residual populations. The L21 Haplogroup is well represented in the DNA databases (likely due to the number of Irish Americans searching for roots) and a number of subclades have been identified below L21 . Most of these subclades have origins in Ireland and are associated with Irish Clans (see: https://www.surnamedna.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/DNA-vs-Irish-Annals-2014.pdf) and developed after L21 arrived in Ireland. My 2012 National Geographic DNA test tested for many of these but I was not positive for any of the main Irish subclades (see below).

Figure: L21 Subclades (2013) with the SNPs National Geographic tested as Negative underlined in red. A negative test at the top of the SNP tree rules out the subclades below.

National Geographic DNA Matches

In addition to testing for SNPs the National Geographic DNA results also include SNP results for mtDNA and Y-DNA. As part of their analysis they plot your closest matches for each (this feature no longer exist on the National Geographic Site) . Unfortunately, only a few of these matches shared their personal information (family origins). For those Y -DNA matches that did give information on family origin the results are:

- On my father’s side, my ancestry is primarily German and Austrian

- My great-grandfather was from the Rhine Valley, Wachenheim an der Rhein

- My dad’s ancestors as far back as northern England, then to Northern Scotland. Our most distant “Traceable” ancestors on my fathers side, were probably Nordic.

- The direct male line of my fathers side was from the Stuttgart area in Germany

- In 1684, my ancestor boarded a ship in Inverness, Scotland and came to New Jersey

- My father was born in Providence RI. He believed that his family emigrated first to Northern Ireland

- My paternal g-g-grandfather was a tenant farmer in the Lower Ards, County Down, Ireland. Surname: Gordon [my note: Scottish surname with Norman roots]

- Paternal line: gggg grandfather born mid 1700s in North Yorkshire, North-East England. My surname is found at highest frequency in various parts of Northern England and South-East Scotland. I have read that it’s associated with the ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia (North-East England) – not sure of the evidence. Paternal line were mainly blonde and blue-eyed

- My father was born in Scotland, but his family is wholly Irish in origin. His paternal grandparents hailed from the area north of Monaghan Town, Co. Monaghan.

- My great-grandfather was born in Rosignol, Belgium.

- Family has possible links to Kent, England

Although there is insufficient data to make a definitive conclusion, this data does suggest closer Y-DNA (Newell family) links to either northwest Europe or the English /Scottish border region than to Ireland. Given the absence of any uniquely Irish L21 subclades and my Y-DNA SNP results, the National Geographic test suggested a possible family origin in Scotland or northwest Europe. It might also suggest possible migration between these areas. In addition, some of this English/Scottish group may have subsequently migrated into Ireland during the 17th and 18th centuries. Given the above, my Newell ancestors that moved to Newfoundland in the 18th century may have originated from any of these areas.

YSEQ L21 Test Results

Research has been ongoing since I did the National Geographic test and new subclades have been identified. I recently (2018) did a new test for L21 subclades with the company YSEQ . The results of my YSEQ DNA L21 Superclade Orientation Panel test identified my final Haplogroup as R1b-FGC17907* with all currently known (2018) downstream branches confirmed negative. FGC17907 is downstream of DF13 and was not identified when I did the National Geographic DNA test. The tree for FGC17907 is: L21>DF13>Z39589>S1051>FGC17906>FGC17907. Currently only a handful of people have tested positive for FGC17907 and there is very little info on this Haplogroup.

Recently (2022) a Newell 3rd cousin did the Familytree DNA Big Y test and tested positive for R-FGC17866 a subclade of R-FGC17907 (Note: marker FGC17866 is currently considered coincident with marker FGC17880). These markers below R-FGC17907 have been identified after I did the YSEQ test. The Genetichomeland.com Web site provides the following map of these markers.

| 41 | S1051 | BY41243 S1051_1 rs772934710 | Under L21. FTDNA position does not match YSeq. |

| 42 | FGC17906 | rs924757637 | |

| 43 | FGC17907 | rs924018074 | Under Z39589 and FGC17906 on YFull and FTDNA trees. |

| 44 | FGC17890 | rs924143424 | Under Z39589 and FGC17907 on FTDNA tree. |

| 45 | FGC17880 | R-FGC17880 rs948241721 | Under Z39589 and FGC17890 on YFull and FTDNA trees. Example is YF092724 from France.Marker [FGC17866] currently considered coincident with marker [FGC17880], using that phylogenetic tree. |

Moving up the tree structure the bulk of the people who are L21 belong to subclades below DF13. The largest of these DF4 and DF21 are most common in Ireland and account for almost half of the individual in Ireland who have tested for L21. Another subclade L1335 is the largest subclade in Scotland and Z253 is the largest in continental Europe. My Haplogroup (FGC17907) likely shared a common ancestor with the S1051 haplogroup and developed sometime after S1051. The S1051 mutation associated with this group is approximately 3,200 to 4,500 years old and likely originated within what is known as the Bell Beaker culture. Based on this, research on S1051 likely represents the best option for understanding the origins of my Haplogroup. The following Diagram shows the location of S1051 in the L21 tree structure (subclades I have tested positive for are circled in red).

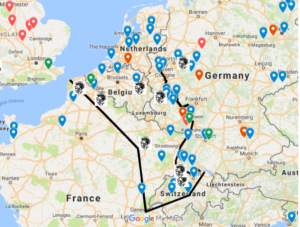

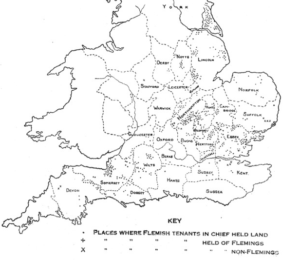

FamilytreeDNA has a project group for S1051 individuals and this site contains data for over 100 individuals who have tested positive for S1051 or one of its subclades. Many of these individuals provide information on their family origins and the most common European origin given is England followed by Scotland and then Ireland. If adjusted for population Scotland would have the highest frequency especially in the Argyll area (west of Edinburgh on map). A subset of these individuals give a town or county where their earliest ancestor originated and I have prepared the following map showing these locations.

The map under represents the Irish data since very few of the people reporting an Irish ancestor gave a detailed location. In terms of my family history the cluster in Somerset and Bristol (see my paper on Newalls of Bristol Channel Region) is especially interesting as is the one record from Jersey (note other records from Brittany and Normandy not shown).

On various Internet discussion groups (e.g anthrogenica.com S1051 Forum) there is speculation regarding a Scottish origin for S1051 given the high concentration of S1051 individuals in the Argyll area of Scotland. However, the STR data (see FamilyTree Y-DNA STR Test below) for these individuals suggest that the common ancestor for many these Argyll individuals was born somewhere in the 500 -1500 yr BP range. This suggest that either there was a genetic bottleneck (population crash) around this time or this was when S1051 individuals first arrived in this area. The 500-1500 BP time frame is when various Norman families arrived in Scotland. The descendants of one of these, Clan Stuart of Bute , became established in the Isle of Bute, the Isle of Arran and the Isle of Cumbrae. The Stewards or seneschals of Dol in Brittany came to Scotland through England when David I of Scotland returned in 1124 to claim his throne. In Scotland they rose to high rank, becoming High Stewards of Scotland. The ancestor of this clan was likely Alan FitzFlaad, a Breton who came over to Great Britain not long after the Norman conquest. Alan had been the hereditary steward of the Bishop of Dol in the Duchy of Brittany. His descendants, the Fitz Alan family, held lands in England, the Welsh border and Scotland. If the Fitz Alan family or their followers carried the S1051 mutation this would explain the distribution in England and Scotland. It would also explain the distribution in Ireland since the Normans settled parts of Ireland (Wexford) around the same time period plus there was later (1500-1700) migration from England and Scotland to Ireland.

If this theory is correct then the Argyll S1051 DNA cluster can be traced back to individuals living in Brittany some time prior to 1066. This is not evidence that the S1051 mutation developed in Brittany since the mutation first appeared approximately 2200 – 3500 years before 1066; however, it does suggest that the mutation may have developed in mainland Europe. In the Familytree S1051 DNA data there are two records identified as Breton plus one (Vaillancourt) that is likely from Normany and one from Jersey. When evaluating the the French records we also need to adjusted for the under representation of European DNA in most databases. Brittany is a good candidate for the home of the Scottish S1051 since it has the highest concentration of L21 DNA in continental Europe (see earlier map) and FamilytreeDNA places S1051 in the Bell Beaker (continental) category rather than the Celtic category. However, Brittany may not be the area where S1051 first developed. In the centuries immediately prior to 1066 both the Franks and Normans had invaded Brittany plus in the 5th-7th centuries Celtic Britons from the south west of England, Cornwall and Wales settled in Brittany. Any of these could have brought S1051 to Brittany.

There are also a number of other S1051 individuals in the data bases listing their origin as Denmark, France, Germany, Portugal or Spain. If adjusted for the under representation of European DNA on these sites then this subclade of L21 has a significant European component. Some of these individuals might have carried S1051 to these areas through trade (i.e. Baltic trade to and from England and Scotland) or the extensive trade from British, Irish and French ports to Iberia (wine, wool, wheat, salt, iron and Oak for wine barrels).

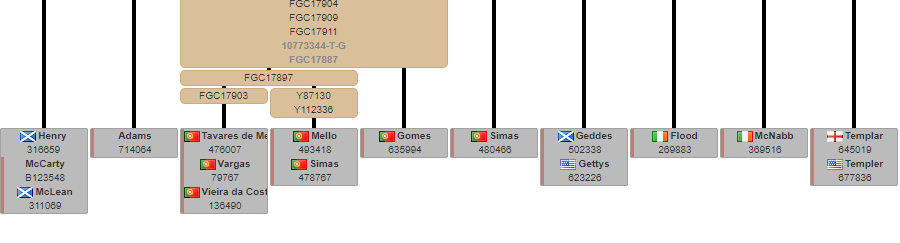

The marker FGC17906 falls between S1051 and FGC17907 (the marker that currently defines my terminal Haplogroup). The FGC17906 data from the FamilytreeDNA S1051 Site includes mainly Scottish names: McAlpin, MacAlpine, McCauley, MacLea, Duncan, Henry, Mclean, McCain, MacKeen and McCormick plus a number of English/Irish names and three Iberian names Costa, Miranda and Calvo which are also positive for FGC17907.

My terminal Haplogroup FGC17907 is based on a SNP two levels below S1051 that was only identified relatively recently. There is very limited published data for FGC17907. The Family tree S1051 site only lists 6 family names for FGC17907:

| Costa | Miranda | Calvo* | McAvoy | Shannon | Fox |

Based on the Iberian links this grouping has been refereed to as the Iberian Gaels (See Chandler S1051 site on FamilytreeDNA). Regarding the Iberian connection the “Big Tree” Web Site provides more information on individuals with the FGC17906 marker (between S1051 and FGC17907). The largest number of matches recorded for FGC17906 at “Big Tree” (see below) were from individuals with Portuguese (mainly Azores) ancestry, followed by Scottish. The link between Scotland and the Azores apparent in the “Big Tree” data for FGC17906 and the Family Tree DNA data for FGC17907 might come from Scottish merchants / “soldiers of fortune” who became established in the Azores as early as the late 1400s:

One possible Scottish source for S1051 DNA found in the Azores might be the following: “soldiers of fortune like the Drummonds who were from the royal house of Scotland, and the Betterncourts [Flemish] who had owned the Canary Islands and had traded their claims [in the late 1400s] to Prince Henry for landing holdings in Madeira and the Azores” (source THE AZORES By Eva Newton).

Unfortunately, the SNP markers used for defining Haplogroups only allow us to estimate the earliest date when our ancestor carrying these markers might have lived. However, there is another test that can be done on Y-DNA that can be used to identify more recent relationships between direct male ancestors. These test look for features in the Y-DNA code called short tandem repeats (STR) rather than SNPs used by National Geographic. This test is described in more detail in the next Section of this report ( see FamilyTree Y-DNA STR Test) but for the following discussion of Haplogroups we simply need to accept that differences in STR values between two individuals can be used to estimate the time since they shared a common ancestor ( Time to the Most Recent Common Ancestor).

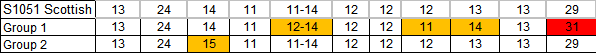

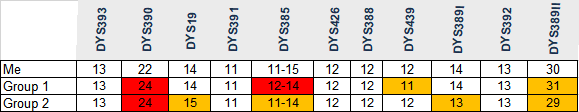

For the S1051 (and subclades) individuals tested with Family Tree DNA we have access to their STR values that provide more information on more recent relationships (I could not find STR values for BigTree results). The values for the first 12 Family Tree STR markers for the 6 FGC17907 individuals (see above) clustered into two groups (McAvoy, Shannon & Fox in Group 1 and the three Iberian individuals in Group 2) with the same STR values within each group. The similar values for individuals in each group suggest that the individuals within each group likely share a common ancestor who lived sometime within the last 500 years. The following Table compares the STR values for Group 1 and Group 2 with the Modal values for the Scottish S1051 cluster on the FamilyTree S1051 Site.

Comparing Group 1 and Group 2 to the Modal STR values for the S1051 Group it is apparent that the Iberian Group (2) is closer to the modal values for S1051 than Group 1. The common ancestor for the Iberian Group 2 and the Scottish Modal group likely lived within the last 200-800 years; however, the common ancestor for the Scottish Modal Group and Group 1 lived in he more distant past. Currently there are no age estimates for the founding of FGC17907 but Haplogroup FGC17906 (between S1051 and FGC17907) is estimated to be 2900 years old. From this we can estimate that the common ancestor for the two groups likely lived some time between 500 and 2500 years ago. The following Table compares my STR values with those for Group 1 and Group 2; it demonstrates that my values are even further removed from both groups than they are from each other.

The difference in STR values between the Iberian Group and the Modal S1051 can be explained by Post 1400 population movements however Group 1 likely diverged from the Scottish Modal Group no later than the Norman invasion (1066) and possibly earlier, Group 1 has an Irish / English bias but on the FamilyTree S1051 Site the Modal S1051 data for Ireland is similar to that for Scotland. The FamilyTree Irish Modal S1051 data may reflect Scottish migration to Ireland in the 1600s and 1700s; however, Group 1 might represent a separate branch of the Norman invasion that went directly to Ireland/England or an even earlier Roman or Pre-Roman migration. In this case the common ancestor might have lived 1000-2500 years BP.

If the Modal S1051 values for Scotland represent a Norman era migration from Brittany to Scotland and the Iberan Group 2 is a later offshoot of this migration and Group 1 represents a separate Irish/English migration then my STR values, that differ from all of these, might represent a separate branch of FGC17907 that split off sometime between 1000 and 2500 years ago.

FamilyTree Y-DNA STR Test

The focus of the National Geographic test is using SNPs to identify Haplogroups that can be used to map longer term migration routes for early people and it is not designed to track family origins; however, other test exist that are better suited to this purpose. These test focused on Y-DNA and test for short tandem repeats (STR) found on the Y chromosome rather than SNPs used by National Geographic. In 2012 I did a 12 marker Y-DNA STR test with FamilytreeDNA (upgraded to a 67 marker test in 2013). The STR tested by FamilytreeDNA are sections of the genetic code that get repeated and are passed down from father to son with the Y-DNA. Only males have Y chromosomes and these get passed from father to son and so can be used to track family name connections. Like SNP these STR can be used as markers to identify groups of people. They differ from SNP in that they change over shorter time frames than SNP and can be used to track more recent family groups . These markers are scattered through your genetic code and are identified by the letters DYS followed by a number e.g. DYS-390 and have a value that indicates the number of repeats. The number of repeats in each marker remains relatively constant from one generation to the next so can be used to track relationships (see following).

STR’s occur at specific locations on the y-chromosome, which are often referred to as loci, and are given names such as “DYS391.” STR’s occur when short segments of DNA sequences get repeated over and over along a portion of a chromosome. For example, DYS391 consists of repeats of the base sequence -GATA-. Once an STR exists, it may change by adding or subtracting a repeat or two during the replication process. Estimates of the frequency of changes range from less than 2 mutations per 1000 generations to over 7 per 1000 generations for each STR, depending on which marker. Thus over a long period of time, individuals will tend to have at least some differences in the values (number of repeats) on the various STR markers on their y-chromosome. If you look at 25 markers, there is about a 50% chance you will find at least 1 mutation in 9-10 generations (or, counting both up and down from the common ancestor, between yourself and a 4th cousin). DYS391 can have values ranging from 7 to 14 repeats, with 10 and 11 being common in populations with European ancestry. There have been over 200 STR markers identified on the y-chromosome, but not all are variable enough for genealogical purposes. Testing companies currently test between 10 and 110 markers. https://web.stanford.edu/~philr/Bachman/DNABachman3.html.

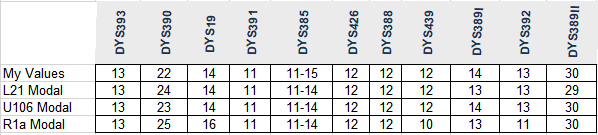

The following Table gives the value (number of repeats) for my first 12 markers tested by FamilyTreeDNA and the Modal values for the L21, U106 and R1a Haplogroups:

Note: In FamilyTreeDNA format DYS389-2 is the sum of DYS389-1 and the underlying value of DYS389-2 so values 14 and 30 for these only differ by one from values of 13 and 29 (in both case the real value of DYS389-2 is 16).

Based on the above, my first 12 markers are closer to the U106 (see earlier map) modal values than they are to the L21 modal values. In the past STR values were used to estimate subclades of R1b but today most companies only use SNPs to determine if someone is L21 or U106.

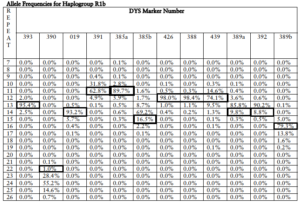

The following Table gives the frequency of different values for each of the first 12 markers in the R1b Haplogroup (my values highlighted):

Source: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.511.7438&rep=rep1&type=pdf

The distribution of the frequency of STR values is such that there is an approximate 1 in 12.5 chance of someone getting the modal R1b values for the first 12 markers by chance. Therefore; assuming that there are 100,000 R1b individuals that have tested the first 12 STR markers and made their data public then there will be 8,000 people with the 12 modal R1b values (same as modal L21) and the true matches will be lost within the noise. This is why the 12 marker test has been generally replaced by the 67 and more recently the 111 marker STR test. However, in my case the STR values are such (further from norm) that the chance of a random 12 marker match is approximately 1 in 100,000; therefore, in my case a match on the 12 markers is a good, but not perfect, indication of a relationship. When I first tested my 12 markers there were only 4 other individuals that were an exact (12 of 12) match. One was my 1st cousin Ted, another was Peter Noel who was from the Harbour Grace Noels (same geographic area as my family), one was a Mr. Clark with roots in Devon, England and the last, Mr Love, had roots in Ireland. Subsequent testing ruled out Mr. Love (different subclade and significantly differences values for markers 13-67 (likely a random match on the first 12 markers tested). Mr Clark and my cousin Ted only tested 12 markers and are now both deceased. In 2017 a 3rd cousin with roots in the Dock (John son of Philip is our common ancestor) did the Family Tree DNA test and we matched exactly on 66 of the 67 markers (what you would expect for 3rd cousins). My value for the different marker (DYS490) is so unusual that I had it retested with a different company YSEQ which confirmed the results which suggest it is a recent mutation. Excluding this one marker this gives a good baseline on the DNA profile for the Newells of ‘The Dock’. A comparison of the 67 marker DNA results for the Dock (using my cousins value for DYS490) with similar data for Peter Noel indicates that there is a 90 % probability of a common ancestor within the last 10-12 generations (likely before the families moved to Newfoundland).

As with most people that test their DNA for genealogical purposes my first line of research was looking for matches (or near matches in my case) with people with the same family name. The distant match with Peter Noel was expected since there was some earlier suggestion of a distant family connection. FamilyTreeDNA has sites where people with the same family name can post their results to search for connections. However, when I compared my DNA (both 12 and 67 markers) with other Newells, Noels, Nevilles, etc there were no matches. The majority of people with these names were separated from me by 4+ markers on the first 12 markers and 20+ on 67 markers. The closest matches were a distance of 3 on the first 12 markers for one Newell (John Newell b. Crosswicks, NJ c. 1804) and one Neville from Cork, Ireland. A distance 3 on a 12 marker test is generally considered to be beyond even a distant family connection.

Given the scarcity of exact matches on the first 12 markers I expanded out looking for people (with any name) with a distance of 1 on a 12 marker test. I used 12 markers since up to recently this was the standard test and has the largest database. In the last few years 67 marker test and even 111 marker test have become more common but there is still a limited number of people who have tested beyond 12 markers. FamilyTreeDNA has a “Y-DNA Ancestor Origins” function that allows you to find the country of origin of people that match you. Using a distance of 1 on a 12 marker test (regardless of Haplogroup) I had 174 matches out of 180,164 people in the FamilyTreeDNA database that reported country of origin. Since this data is not Haplogroup specific many of these matches might not be related to me; what the data provides is a set of matches that may contain my relatives. The results for European countries (Excluding US, Canada, etc) are presented below:

| 12 markers distance of 1 | |||

| Country | Match Total | Country Total | Percentage |

| England | 71 | 40199 | 0.177% |

| United Kingdom | 22 | 14464 | 0.152% |

| Germany | 21 | 21284 | 0.099% |

| Ireland | 12 | 26378 | 0.045% |

| Scotland | 8 | 18909 | 0.042% |

| France | 6 | 6199 | 0.097% |

| Netherlands | 3 | 2801 | 0.107% |

| Spain | 3 | 5490 | 0.055% |

| Sweden | 3 | 6370 | 0.047% |

| Wales | 2 | 3238 | 0.062% |

| Denmark | 1 | 1468 | 0.068% |

| Norway | 1 | 3490 | 0.029% |

| Poland | 1 | 6707 | 0.015% |

| Portugal | 1 | 1673 | 0.060% |

| Russia | 1 | 7636 | 0.013% |

| Totals | 156 | 166306 | 0.094% |

It is important to note that the data in DNA databases have a bias towards North America, the UK and Ireland; this occurs since Europeans are less likely to be tested and to make their data public. For example, the UK and France have similar populations but the Table above has 76,810 people reporting UK origins versus only 6,199 for France. However, by comparing the number of matches to the number of people tested we can adjust for this effect. Using this measure we see that England has the highest ratio of my matches to people tested. Excluding the UK (mixture of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) the next highest region is the Netherlands followed by Germany and France. Unfortunately, the FamilyTreeDNA site is limited to people who have tested with them and has limited capabilities to search.

Y-Search Mapping

There is a 3rd party site (www.ysearch.org) that FamilyTreeDNA allows people to upload their results to and which contains data from other testing companies. This site also has better search capabilities. The Y-Search DNA databases allowed me to filter down to people that gave location data below the country level (e.g. city, county or sub country region) . I did not include people who gave their origin as just England, Scotland or Wales. I used this data to map people in the UK and Ireland with a distance of 1 on my first 12 FamilyTreeDNA markers. A match within 1 on a 12 marker test is not evidence for a close family connection (none of these had one of the related Newell family names) but might suggest distant relationships (common ancestor) over longer time frames (e.g before family names became standard in the 15th century). Only some of there people in the database were aware of their family origins (many like me just suspected origins in the UK) and some did not share information on origins. To correct for this I used other data on the Web (e.g. family name groups) and e-mail followup with individuals to get more information on their family origins. I did a similar search 5 years ago and surprisingly many of the people in that search were no longer in the database so I merged the old and new data. To adjust for the under reporting in mainland Europe compared to the UK, I included matches that differ by a distance of 2 out of 12 markers for mainland Europe. This also helps to capture possible earlier European origins (>1000 yrs BP). The following map shows the data for the UK, Ireland and mainland Europe. Matches with a distance of 1 are indicated in red, those with a distance of 2 in blue (only plotted for Mainland Europe) and National Geographic SNP matches are in green.

The UK data had a cluster in the North and Midlands of England (with outliers in Scotland, Ireland and southwest England). Given the location of the UK cluster it suggest that the Newall spelling should be considered since it is more common in this area. Again, I should emphasize that a match at this level is not strong evidence of a common ancestor but just suggestive. In terms of the variation from my 12 marker values most of the variation was in three markers DYS390, DYS385b and DYS389-1; these three markers are the ones where I am furtherest from the R1b norms.

There is more discussion of the UK and Irish patterns later in this report. I have shared a Google Map (follow link) that contains all the UK and Irish data. The blue symbols show UK and Irish matches with a distance of 2 out of 12 markers. These distance of 2 matches follow the same pattern as the distance of 1 matches (in Red) except for additional small clusters near Chester, Bristol, SE England, SW Scotland and SW Ireland (Cork).

The mainland European data (especially the difference of 2 data) clusters in the Netherlands, Belgium, northwest Germany and the area along the Rhine River. There are also outliers along the Atlantic coast of France and Eastern Europe. While this pattern does not appear to fit any particular modern political area it does fit exceedingly well with an historical region. The following map shows the European DNA data and the boundary of the Roman province of Belgica (Belgium gets its name from the same root).

Note: the Roman head symbols on the map represent Roman centers manned by Belgae,

The Data cluster along the Rhine fits the eastern boundary of Roman Belgica. In addition, a review of the history of this region and it’s people (see following) can explain many of the outliers. Migration from Flanders between 1200 and 1600 may be responsible for the DNA matches (see map) in NE Germany and the Baltic region. For example:

- From the 13th to the 15th centuries, Prussia invited several waves of Flemings along with Netherlands Dutch and Frisians to settle throughout the country (mainly along the Baltic Sea coast). In the 12th century, Fläming , a region in Germany southwest of Berlin in the historic state of Brandenburg was subsequently named for them (https://books.google.ca/books?id=IqKCBgAAQBAJ);

- A landmark of Potsdam is the two-street Dutch Quarter (Holländisches Viertel), an ensemble of buildings that is unique in Europe, with about 150 houses built of red bricks in the Dutch style. It was built between 1734 and 1742 under the direction of Jan Bouman to be used by Dutch artisans and craftsmen who had been invited to settle here by King Frederick Wilhelm I (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holl%C3%A4ndisches_Viertel);

- In 1595 Duke Karl, requested the help of his Belgian friend, Wellam de Besche, to help develop the metallurgy industry of Sweden. After Karl became king in 1599, many Walloon immigrants arrived in Sweden to help achieve the royals’ dreams of developing the Swedish industry (https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Vallons_in_Sweden);

- In the High Middle Ages, groups people migrated to Pomerania during the Ostsiedlung. These migrants, consisting of Germans from what is now Northwestern Germany, Danes, Dutch and Flemings gradually outnumbering and assimilating the West Slavic tribes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostsiedlung_in_Pomerania).

The migration of Flemings might also explain some of the DNA outliers in Southeastern Europe since Flemings also represented a small proportion of German-speaking Transylvanian Saxon settlement in the Romanian region of Transylvania, then under Austro-Hungarian rule from the 16th to 18th centuries. The Austrian Hapsburgs, who ruled the Spanish Netherlands and Spain, might also be responsible for some of the DNA matches in Spain by moving people around their empire. The movement of Protestants away from regions annexed by Catholic France during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries may explain the clustering of DNA matches along the northern and eastern border of Belgica.

Belgica and the History of Europe

The Roman province of Belgica (AKA Gallia Belgica) gets its name from the Belgae; a tribal confederation that occupied this area before the Romans arrived. Much of what we know about the Belgae comes from Roman sources including Julius Caesar. Caesar had direct contact with the Belgae; having been almost defeated by the Nervii , one of the Belgae tribes, at the Battle of the Sabis in 57 BC.

Caesar’s comments on the Belgae have caused confusion over their ethnicity. He describes them as different from the Gauls in language. He says that the bulk of them descended from tribes which long ago came across the Rhine from Germania. Yet their recorded tribal, personal and place-names are Celtic… They seem to have spoken a language similar to Gaulish… It seems that the Belgae had pushed into North-East Gaul from what had been Celtic-speaking lands east of the Rhine, under pressure from the expanding Germani. Thus their ancestry was from what the Romans called Germania, but they were Celts (https://www.pri.org/stories/2015-12-30/dna-solves-mysteries-ancient-ireland).

Basically, the Belgae occupied a transition zone between the proto-germanic tribes east of the Rhine and the Gauls (later French) to the southwest. Some researchers have even proposed that they were a separate people with a language that was neither Germanic or Celtic (See: Nordwestblock). It might not be a stretch to imagine the Belgae as a offshoot of the L21 people that crossed into Britan and Ireland around 2500 BC that remained behind and integrated with their U106 (proto-germanic) cousins in northwest Europe. It is clear that the Belgae were not a single people (they were made up of a number of different tribes) and might have included sufficient L21 people to account for the 10% of the modern population in Belgium and the Neatherlands with the L21 Haplogroup. Remember, Y-DNA has very little to do with how we look (autosomal DNA accounts for this), language and culture. Both language and culture can be associated with Haplogroups but are really determined by the other people in the area where you live (after several generations most immigrants to the US are closer to ‘American” cultural norms than to the culture of their ancestors).

For several centuries prior to their defeat by the Romans the Belgae had their own period of expansion and colonization. The Belgae tribes that lived along the coast of what is now Belgium and the Neatherlands were seafarers (The name of one Belgae tribe the Morini is thought to be Celtic meaning “those of the sea”). These Belgae tribes were perhaps the first ‘Viking’ style Raiders and established colonies along what is now the Atlantic coast of France (Normandy area); in southwest Britain and possibly in Ireland. Again we most rely on the Roman’s for our knowledge of these early Belgae colonies. When the Roman’s conquered Britain the Belgae were established in the area from the Isle of Wight to Bristol (see map below).

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgae).

In Normandy there is a Belgae archaeological site at Camp du Canada, Fecamp, France. The situation in Ireland is less well defined since the Romans never occupied Ireland; however, there are indications from the Irish annals and archaeological research that Belgae tribes colonized parts of Ireland in the centuries leading up to the Roman invasion of Britain (possibly the Fir Bolg culture). This was up to 2000 years after the initial L21 “Celtic’ migration into Ireland.

The Roman conquest of the Belgae did not end their story but deepened it. The Romans respected the fighting capabilities of the Belgae and soon incorporated them into the Roman Legions that defended Roman Gaul from the Germanic tribes east of the Rhine. Belgae troops were stationed along the Rhine (as far south as present day Switzerland) and were incorporated into the Legions sent to defend Britain. The First Nervian Cohort in Britain (the Nervii were a Belgae tribe) was one-thousand strong and there were three other Nervian Cohorts in Britain https://books.google.ca/books?id=X9PGRaZt-zcC. These Nervii were stationed along the borders of Roman Britain ( Hadrian’s Wall and Welsh border). Another Belgae tribe the Treveri or Treviri (from the lower valley of the Moselle) also supplied troops for the Roman Garrisons in Britain. The Treveri supplied the Roman army with some of its most famous cavalry and interestingly there was a monument to one Insus son of Vodullus, citizen of the Treveri, cavalryman of the ala Augusta found in Lancaster, England http://collections.lancsmuseums.gov.uk/narratives/narrative.php?irn=95.

The inscription on the monument states that Domitia his heir had this set up which indicates that these Roman auxiliary troops were established in Britain and had families. Given that the Roman period in Britain lasted more than 300 years it is possible that these Belgae troops lived in Britain for many generations. It is also likely that although most true ‘Roman’ troops left Britain around 400 AD many of these auxiliaries and their descendants were left behind. In the last decades before the last Roman troops left Britain they were pulled back from the northern border (Hadrian’s Wall) and likely concentrated around the major Roman towns in the north (Chester, York and Lincoln).

The Roman withdrawal from Britain was a result of pressure from Irish, Welsh, Scottish and Saxon tribes. After 400 AD the Anglo-Saxons and later the Danes started to settle in Britain. The Germanic people who settled Britain were not a single group but were a mixture of Saxons, Angles, Jutes and Frisians. During the period when the Saxons were first settling Britain (400-500 AD) it is possible that these settlers included some people from coastal Belgica; however, it will be another 600 years before there was significant migration from Belgica to Britain.

At the same time as the initial Anglo-Saxon raids on Britain the Germanic tribes started to push into Roman Belgica. The Saxons were pushing down from the northeast and the Ripuarian Franks were moving in from the east. Even before this period the Romans had allowed the Salian Franks to cross the Rhine and settle in what is now the Netherlands. Over the next 300 years the Salian Franks morphed into the Merovingian dynasty eventually merging with the Ripuarian Franks to become the Kingdom of the Franks, By the end of the 8th century the Franks had absorbed the Saxons into their empire (see map).

Note Re Map: Austrasia was a territory which formed the northeastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the Ripuarian Frankish tribes prior to the unification of all Franks under the Salian Franks.

In 771 AD Charlemagne was crowned King of the Franks, and in 800 AD Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor of the Romans. Charlemagne ruled his empire from lands that were formerly parts of Roman Belgica. Considering that the Belgae considered themselves to be Germanic (and spoke a similar language), it is not unreasonable to assume that they integrated into the Saxon and Frankish culture.

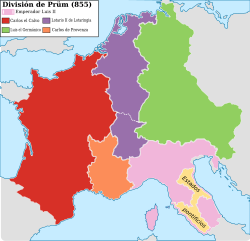

Charlemagne’s Empire survived until his grandsons divided the empire into three parts in the mid 9th century.

By this point most of Roman Belgica was in the Kingdom of Lotharingia comprising the present-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany), Rhineland-Palatinate (Germany), Saarland (Germany), and Lorraine (France). Lotharingia, like Roman Belgica, was a buffer zone between the Germanic and proto-French speaking parts of Charlemagne’s Empire. By the 10th century Lotharingia was further divided (see map below) .

This map shows Flanders, originally part of Roman Belgica, as part of France; however, it’s unique history kept it separate (see following):

The county of Flanders began with Judith (844-870), daughter of the Carolingian king of the West Franks and Frankish Roman Emperor, Charles the Bald. Charles was one of Europe’s most powerful kings in the ninth century, having inherited the westernmost third of the mighty Carolingian empire following the Treaty of Verdun in AD 843. Judith married twice to English [Saxon] kings of Wessex (first to Aethulwulf and then to his son). Later she returned to the continental mainland and eloped with Baldwin Iron Arm. Charles disapproved, but Judith could not be induced to return so Charles relented and granted Flanders to the two of them. Source: http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsEurope/FranceFlanders.htm.

Baldwin married Judith and was granted lands, which would evolve into the County of Flanders. Bauldwin was a Margrave (a medieval title for the military commander/duke assigned to maintain the defense of one of the border provinces of a kingdom). At that time the Vikings were raiding along the coast and the French needed Bauldwin to protect their northern border. Flanders nominally belonged to the kingdom of France but the Margraves (later Counts) of Flanders exercised considerable independence. In 911 AD the Viking leader Rollo, who had invaded France, became the Duke of Normandy and assumed a similar role.

In 1035 Baldwin V became Count of Flanders. By this time the Counts of Flanders played a pivotal role in French politics. From 1060 to 1067 Baldwin was the co-Regent with Anne of Kiev for his nephew-by-marriage Philip I of France, indicating the importance he had acquired in French politics. Baldwin was also father-in-law to William, Duke of Normandy (William the Conqueror), who had married his daughter Matilda. Flanders also played a pivotal role in Edward the Confessor’s (Saxon King of England) foreign policy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baldwin_V,_Count_of_Flanders .

When William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 Flanders remained technically neutral but Bauldwin V did not stop many of his lesser Nobles from supporting his son-in-law William the Conqueror. There are few written records of Flemings accompanying William in 1066 but analysis of Flemings holding Estates after the conquest show that they were likely well represented (see map).

After the conquest two Flemmings held important post in northern England. Gerbod the Fleming became the 1st Earl of Chester and Gilbert de Gant (Ghent) became Earl of Lincoln. Gerbold subsequently returned to Flanders where he fell into the hands of his enemies and was held captive; as a result King William I gave the earldom of Chester to a Norman Lord. Not all Flemings that came with William became Earls, many minor officials and foot soldiers received smaller holdings. One of these was Archibald (AKA Erchenbald , Archembald) le Fleming who received holdings in Devon (Bratton Fleming near Barnstaple). Richardle Fleming, son of Archibald Fleming, of Devonshire, attended the Norman lord Hugh de Lacy to Ireland (https://books.google.ca/books?id=jkdfAAAAcAAJ). Hugh de Lacy had substantial land holdings in Herefordshire and Shropshire, in England and following his participation in the Norman Invasion of Ireland (in 1172) he was granted the Lordship of Meath by Henry II. Undoubtedly, other Flemings found their way to Ireland with the Normans. There is also a Scottish connection to the Flemings of Bratton. Baldwin the Fleming is thought to have been the son of Stephen Flandrensis of Bratton in Devonshire, expelled by Henry II in 1154. Baldwin became sheriff of Lanarkshire (scotland) and lord of Biggar, constructing a castle there (http://flemish.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2015/12/04/flemish-migration-to-scotland-in-the-medieval-and-early-modern-periods/) .

In 12th and 13th centuries Flanders prospered as a center for cloth production. In 1302 the city states of Flanders defeated the French army at the Battle of the Golden Spurs. Two years later, the uprising was defeated and Flanders returned to control by the French Crown. In 1384 Flanders was united with Burgundy, and by the mid-15th century the Dukes of Burgundy ruled the greater part of the Belgian and Dutch Netherlands and lands along the Rhine (see map below).

Western Europe in 1470 ( http://www.vlib.us/medieval/lectures/hundred_years_war.html)

While owing allegiance to the French crown, Burgundy’s aim was to found a powerful state between France and Germany. This effort was disrupted by the death in 1477 of the last Burgundian ruler, Charles the Bold http://www.countriesquest.com/europe/belgium/history.htm. By 1556 the Burgundian Netherlands were being ruled by the Catholic Habsburg kings of Spain (successors to the Burgundians). By this time Flanders had been removed from the territory of the Kingdom of France, except that some western districts of Flanders came under French rule under successive treaties of 1659 , 1668, and 1678. Flanders ended up, uniquely, as the only territory that began the Middle Ages as part of France but ended them, as it still is, alienated from France. Today, most of historical Flanders, except for Picardy, is part of Belgium Source: http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsEurope/FranceFlanders.htm.

The connections between Flanders and England did not end with the Norman invasion.

Flanders suffered greatly after a series of storms. During a tremendous storm on the coast of Flanders, the sand hills and embankments were in many places carried away, and the sea inundated a large tract of country (Samuel Lewis) . This led a large number of Flemings to seek asylum in England, where they were welcomed by Henry I.

From the 13th century up to ~1500 various English Kings attempted to develop a cloth industry in England (at this time English cloth was poor quality and production was low). To overcome this they encouraged Flemish weavers to move to England. This migration was also spurred by the political upheavals in Flanders.

Flemish influence, however, can be postulated from an early date. Flemish weavers seem to have settled in the towns which grew up around the new Norman castles after the Conquest. Drogo of Bruere, a Fleming, obtained a large grant of land at Beverley from the Conqueror, and there was soon a settlement of Flemish weavers in that town, where they have given their name to the Flemingate. ‘Gilbert the Weaver and Baldwin the Tailor’ are names figuring in the list of settlers around the new abbey of Battle, and the names and trades seem to mark them down as Flemings. The evidence as to the gilds of weavers in London, Winchester, Marlborough, Beverley, and Lincoln, and the special disabilities of the weavers and dyers seem to show that they were aliens organized as a separate community under the protection of the crown. When in 1270 the wool trade to Flanders was interrupted, Henry III sought to induce Flemish weavers to settle in England, and with some success; for when a little later he issued orders to all Flemings to leave the country, he excepted ‘those workmen, who with our leave shall come into our land to make cloths’. The Norfolk worsted industry was founded at some date prior to 1315, probably with some settlement of Flemish weavers at the village of Worstead. (Source: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/llew001infl01_01/llew001infl01_01_0011.php).

There is one story that Philippa of Hainault, the Flemish wife of Edward III, had recommended the introduction of the weavers into England. (note: Her son was John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (b. 1340) whose male heirs include English kings Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI (House of Plantagenet). He was called “John of Gaunt” because he was born in Ghent, Belgium).

“The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester A.D. 1363” by Ford Madox Brown, a mural at Manchester Town Hall. – http://www.manchester.gov.uk/townhall/venues/murals1.htm

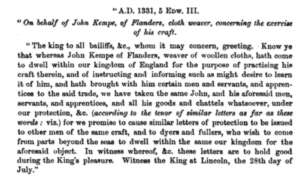

In 1331 special protection was granted to John Kemp a weaver of Flanders (possibly from Hainault, where Edward’s father in Law was the Duke) to settled in Kendal, Westmorland, England,

Kemp was much more than a simple weaver since it was reported that he brought 70 weavers and their families to Kendal ( https://books.google.ca/books?id=6uVhAAAAcAAJ).

During this period Flemish weavers also settled in other areas of England, Scotland and Ireland, here are a few examples:

- Honiton, Devon grew to become an important market town, known for lace making that was introduced by Flemish immigrants in the Elizabethan era;

- A census from 1440 shows French, Dutch and Flemish immigrants in south Devon port towns;

- Three Flemish weavers from Diest in Belgium lived and worked in St Ives, Huntingdonshire, in the 1330s ;

- In 1587 the Scottish Parliament passed a law in that encouraged Flemish weavers to come to Scotland;

- Roger Boyle, Earl of Orrery brought Dutch settlers to Ireland in 1660.

In addition, numerous UK families trace their roots back to Flanders; for example: The Doel family are almost certainly descended from Flemish Weavers from the village of Doel which is on the outskirts of Antwerp, Belgium. Their immediate ancestors came from the Westbury/Trowbridge area of Wiltshire to Minchinhampton in Gloucestershire c. 1500s (http://www.users.greenbee.net/~noelbaker/doeltree.htm) .

This pattern of early (pre 1600) immigrants assuming the name of their home town as their surname when they arrived in England was not uncommon. Early English records frequently identify immigrants by their first name and the town they came from. Several towns in areas linked to Roman Belgica (including the Normandy region of France) have names related to Newell. These include:

- Newel and Bad Neuenahr [Nieuwenaer] in Germany;

- Nevele and Nivelles, Belgium [in England Neville frequently transcribed as Newell];

- Nieuwaal (Newly), Netherlands;

- Neuville-Ferrières, Néville and Néville-sur-Mer in Normandy.

From the perspective of the Newells of ‘The Dock’ it is also significant that some have speculated that Béthune, France (near the border with Belgium and 86 km from Nevele) may be the origin of the Batten name and that Beauchamp, Belgium may be the origin of the Beacham name.

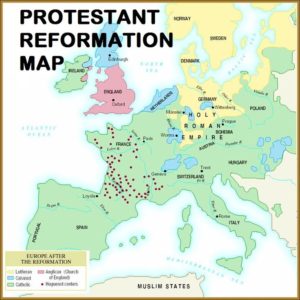

The start of the 16th century in Europe was marked by the start of the Protestant Reformation which split Europe into two irreconcilable camps. The map below shows that most areas that were formerly Roman Belgica reverted to their former role of border states but this time separating Protestant from Catholic Europe. This position between these two irreconcilable views of the world would force many residents of these areas to flee their homelands.

One result of the Protestant Reformation was that Catholic France underwent a major internal upheaval that led to the French Wars of Religion that extended from 1562 to 1598. It is estimated that three million people perished in this period. During these wars the majority of the Protestant French Huguenots were either killed, converted or fled France. This purging of Protestants from France combined with France annexing territories along its northern and eastern border (parts of Flanders and along the Rhine) resulted in many Protestants that lived in former Belegic areas fleeing to either Holland, Germany or the UK. Many religious refugees settled initially in large Protestant cities such as Geneva or Zurich then migrated to England, where Edward VI had in 1550 established London as a location for ‘Stranger Churches’, in which Calvinists from the Low Countries and France could practice their religion among their own people (http://flemish.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2015/12/04/flemish-migration-to-scotland-in-the-medieval-and-early-modern-periods/)

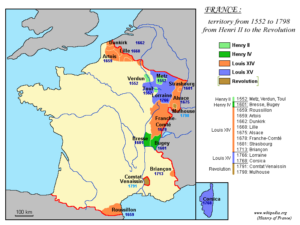

Lands Annexed by France 1552-1798.

Even though Henry VIII broke with Rome in the 1530s Protestant beliefs were not fully accepted in England until the start of Elizabeth I Reign in 1558. Some time between 1539 and the close of Henry VIII’s reign a Nicholas Newell, a Frenchman living in St. Mary Woolchurch Parish, London was arrested for his religious beliefs; he was presented to be a man far gone in the new sect, and that he was a great jester at the saints, and at our Lady (source: Fox’s Book of Martyrs, Vol 2).

Some early English immigration records are available for the years 1330-1550 (see http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/englands-immigrants-1330-1550/) and Newell appears in these as a Surname and a first name (these could be reversed). Some examples include:

| Newell, Colyn | – | 6 April 1440 | – | Norfolk, Ultra Aquam ward |

| Newell, Jacobus | – | 10 September 1451 | – | Middlesex |

| Newell, John | – | 4 April 1440 | – | Bedfordshire, Flitt hundred |

| Newell, John | – | 12 October 1444 | – | London, Bread Street ward |

| Newell, John van | Teutonic | June 1483 | – | London, Dowgate ward |

| Turges, Newell | Fleming | 15 December 1512 | – | – |

| Frenssheman , Newell | French | c. 28 May 1440 | – | Sussex, Whalesborne hundred |

Some related names include:

| Frensshman, Noel | French | 11 July 1440 | – |

Hampshire, Copnor

|

| Nevell, John | Picard | 1 July 1544 | Abbeville |

| Nevell, Philip | Norman | 1 July 1544 [40 yrs in England] | Cherbourg, [Normandy] |

| Nevell, Robert | – | aft. 28 September 1441 | – |

Buckinghamshire, West Wycombe

|

| Nevill, Martin | Savoyard | 1 July 1544 | – |

‘Manhod’

|

| Noell, Geoffrey | – | 12 July 1441 | – |

Kent, Hythe

|

An Internet search found a number of Dutch and Belgium people with names that could become Newell in England . These include:

- Jan van Nieuwaal, in the service of the Dutch East India Company in 1763;

- Jan Rutgers Nieuwal (Niwael), a 17th century Dutch painter;

- Jacob Nouwelsz (NOELL), born Abt. 1599 in Sedan Andennes. France-Belgium, and died Abt. 1683 in Leiden, Holland;

- Johannes Nouwels, born in Drongelen in 1770′ passed away on 10 Jul 1857 in Delft;

- Cornelius Noell (Nowe), born 1622 Leiden, Leiden, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands;

- Justus Hendrik Nevel, married 1786 at Nijmegen, Gelderland, Nederlands;

- Jan Nuls, a Dutch immigrant recorded at London in 1615 (https://books.google.ca/books?isbn=9004089551).

This section still under construction.